CDC doctor who suffered a concussion in scooter accident experiences a new approach to treating brain injury

Woman gets 'crash course' in concussions after falling off scooter

After suffering a mild concussion, but not realizing it, Catherine McLean said life sent her for a loop. She warns anyone who hits their head to be seen immediately.

ATLANTA - Standing inside a high-tech pod at the Shepherd Center Complex Concussion Clinic in Atlanta, as the machine tracks her balance, response times, and hand-eye coordination, Catherine McLean of Dunwoody, Georgia, has a lot coming at her.

"[I'm seeing] lights, colors, motion, flashing," McLean says, describing the Bertec Balance Advantage Computerized Dynamic Posturography system.

It has been almost five years since the CDC epidemiologist and physician made what she now knows was a colossally bad decision to take a scooter for a spin without a helmet.

"I decided to try out a new child's laser scooter in my driveway," McLean says.

She bought two, one for herself and one for her partner Deborah, thinking it would be fun to ride them together in a nearby park.

Her partner thought the scooters were a bad idea.

So, one July afternoon, McLean stepped on the scooter and began to roll down her driveway while her partner was at the pool. As she started rolling, she realized the driveway was steeper than she had thought.

"I stepped on it and got going really fast, unable to stop. [I] hit that bump, that kind of lip at the end of the driveway, and flipped into the street and … landed on my face on the asphalt," McLean says. "It was really quite alarming and disturbing."

McLean did not realize it then, but she had suffered a concussion, or a mild traumatic brain injury.

When her head hit the asphalt, the impact had caused her brain to bounce or twist inside her skull.

"I wasn't blacked out," she remembers. "I didn't lose consciousness. [I] picked up my things, was bleeding, and went back into the house and cleaned up."

McLean took a few days off from work and got her vision checked.

It was normal.

"Again, [there were] no neurologic signs or symptoms, no change in function," McLean says.

But as the days passed, she felt worse.

She had intense migraine headaches.

"I was just getting more and more restless and uncomfortable and felt like something was off," she says.

When McLean suddenly started vomiting several days after the accident, her partner Deborah brought her to the emergency room at Emory St. Joseph's Hospital. She was diagnosed with complications from a concussion and placed in the ICU.

"I was really sick," she says. "I was really uncomfortable, and it only got more so."

After she was released from the hospital, McLean came to Shepherd Center. She underwent a series of tests with the complex concussion clinic's director Dr. Rusty Gore, a neurologist who specializes in treating concussions.

She was struggling with vertigo, migraines, and cognitive deficits.

"This is a silent injury," Dr. Gore says. "It's kind of an invisible injury. So, you know, you don't outwardly look impaired."

Dr. Gore says researchers believe a concussion triggers a chain reaction in the brain, slowing down networks that help us lay down new memories, think critically, balance and navigate the world around us, and regulate our emotions.

In the past, Gore says, doctors would recommend resting the brain, or "caving" in a dark room.

"We're no longer making that recommendation," he says. "So, we know now that getting back to activity, getting back to activity in kind of in the shallow end of the activity pool, is really important right after injury because we need to be moving our bodies. We need to be using our minds. We need to be exercising."

So, McLean began intense therapy to help her cope with the challenges she was facing.

Because of her injury, she would get easily overstimulated by lights and noise, which would trigger her vertigo and headaches.

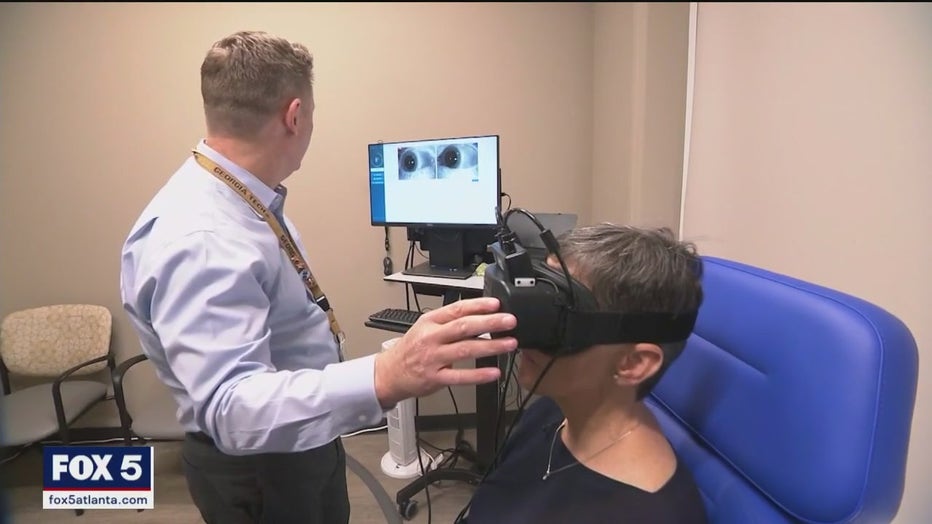

Using virtual reality, she learned how to navigate the shiny floors and bright lights at the grocery store, and how to deal with the sensory overload she experienced in loud, bright settings like Braves' baseball games.

This spring, she and Deborah returned to spring training for the first time, and she had no issues.

"It's great to be able to get back to the Braves, and see them play, and enjoy that pleasure without feeling sick." McLean says.

After several months on medical leave, she was able to return to her work at the CDC.

"I've learned a lot of techniques in working with the computer or phones, when to step back, and how to modify my environment to make things more feasible for me," McLean says.

Last year, after experiencing a recurrence of her symptoms, she returned to Shepherd Center for more therapy.

Catherine McLean is now back at work full-time, and says she's grateful to the team who helped her get there.

"They got me back not only to my baseline level of function, but people in my life who are closest with me feel like I'm even better than I was before," McLean says.

"That's a gift."