Did Coffee County breach put future elections at risk? Depends on who you ask

Coffee County residents gathered to hear warnings about the integrity of their voting system due to the actions of some of their neighbors.

DOUGLAS, Ga. - The role Coffee County played in the election racketeering case not only raised questions about a potential criminal enterprise but the integrity of future elections across the country.

How much should voters be worried that proprietary data from Dominion Voting Systems was secretly copied and publicly shared?

The answer depends on who you ask.

HE BOASTED ABOUT BREACHING ELECTION COMPUTERS, FOREVER LINKING FULTON AND COFFEE COUNTY

Did Coffee County breach put future elections at risk?

The role Coffee County plays in the election racketeering case not only raises questions about a potential criminal enterprise, but the integrity of future elections across the country. How much should voters be worried that proprietary data from Dominion Voting Systems was secretly copied and publicly shared?

Dominion and the Georgia Secretary of State’s Office believe that data breach — while unauthorized — does not a pose a serious threat. They point to the success of the 2022 election, which went off without controversy or cyberattacks nearly two years after the Coffee County incident.

But others see it differently.

"I am extremely worried about the 2024 election," said Olivia Coley-Pearson, a Douglas City Council member and longtime resident of Coffee County.

The now-shuttered Coffee County Elections office where outsiders were allowed to copy Dominion voting software in 2021. The office has since moved locations.

Coley-Pearson was one of about 60 people who gathered at the Gaines Chapel AME Church in Coffee County on a recent Saturday. They were there to listen to a presentation from members of the Coalition for Good Governance, a non-profit, clearly preaching to the choir.

"Praise the Lord for Fani Willis!" exclaimed one member from the stage.

"If we have no accountability, there will be no effective change," echoed a resident from the back of the room.

"We’re worried that this could affect not just Coffee, but the whole state," explained Marilyn Marks, executive director of the non-profit whose work played a vital role in exposing the Coffee County breach.

The Coaltion for Good Governance sued in 2017 to try to get Georgia to ditch its computerized voting system and switch to paper ballots that would be fed into a scanner.

That lawsuit is still ongoing, but has already produced key evidence for Fulton District Attorney Fani Willis. Four of the 19 defendants in the Fulton County case are accused of computer theft in Coffee County as part of the overall alleged criminal enterprise to interfere with the 2020 Georgia election.

Surveillance videos starting January 2021 show different groups of skeptical cyber analysts allowed inside the secured area of the Coffee County Elections Office.

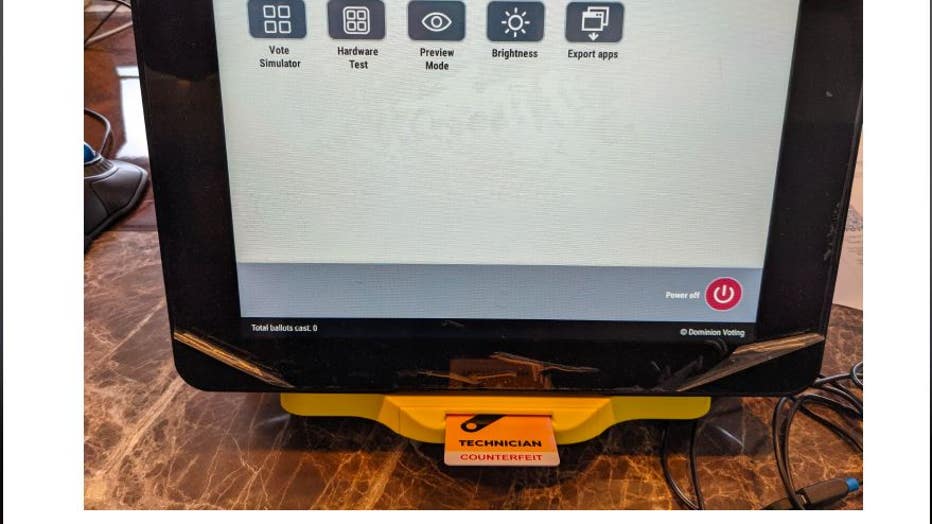

No votes were changed, but some made copies of software neither Dominion nor the state authorized.

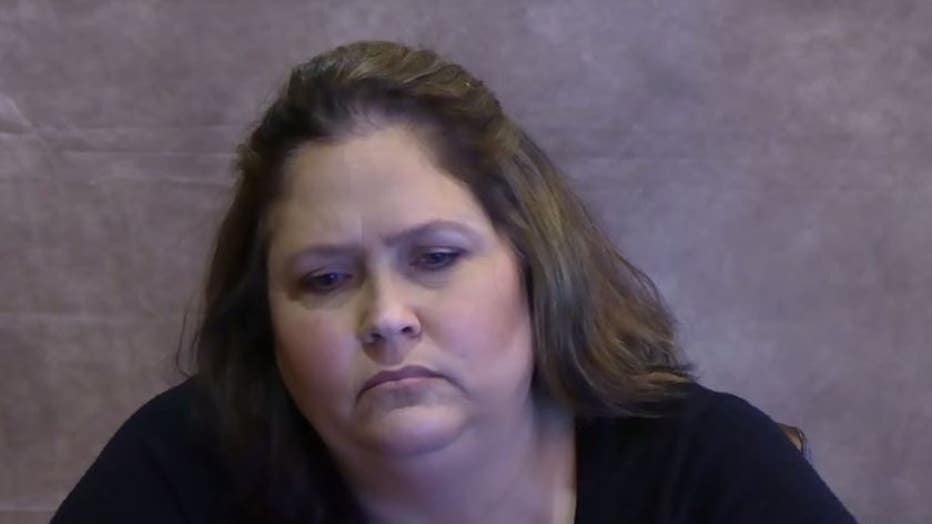

Misty Hampton was questioned about her actions a year before she would be indicted by a Fulton County grand jury.

Others… well, we’re not exactly sure why they were there.

Here's an exchange from the deposition of Misty Hampton, one of the defendants who was the Coffee County Elections supervisor at the time of the breach.

Plaintiff's Attorney Bruce Brown: "Ms. Hampton, why did Mike Lindell also known as the My Pillow Guy come to Douglas, GA on February 21, 2021?"

Hampton: "I plead the Fifth on that."

Hampton was forced to resign over allegations of faking her timesheets, something she denies doing. She argued that she was only following the orders from certain elections board members.

But Hampton is the only Coffee County elections official who is now facing seven counts in Fulton County.

In a series of videotaped depositions from the CGG civil case, Hampton admitted she let various people into her office, including once on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day when the building was closed.

Hampton: "I was the one physically touching the machines, yes."

Brown: "But basically he was trying to figure out how they worked, right? Fair to say?"

Hampton: "I would say so."

Brown: "And did he ask you to make any copies of any of the equipment or the software or the thumb drives or anything else in there?"

Hampton: "I'm going to plead the Fifth on that."

All the equipment involved in the Coffee County voting machine breach has been replaced according to the state.

The Secretary of State’s Office replaced the equipment and server in Coffee County. The GBI is nearing the end of its separate investigation.

And yet there is an irony in Coffee County. Did the people who thought they were exposing evidence of election fraud wind up making future elections less secure?

"The search for voter fraud or election fraud that some of the Trump allies found themselves doing here in Coffee County has in fact created an even more exploitable system," said Marks.

According to court filings, the Dominion data copied in Coffee County and other states have been shared online. A lot.

"So many people have access to it," Marks pointed out. "Can create malware. Create a huge risk for the 2024 election."

An exhibit from the Halderman Report which raised concerns about damage from hackers to Georgia's voting system.

Add to that the release of the Halderman Report this summer, written by an election software expert who was allowed to examine the Dominion system as part of the CGG civil case against the Secretary of State.

The report found a vulnerability in the code "that can be exploited to spread malware from a county’s central election management system."

"This attack is especially dangerous because it is scalable… Attackers do not need access to each individual machine."

That’s why critics want Georgia to go back to bubble-in paper ballots. You would personally feed your ballot into a scanner just like election workers do with mail-in ballots.

"You don’t have to to trust that the computer marked the ballot correctly," said Marks.

A Dominion spokesman said "nearly three years after the 2020 election, no credible evidence has ever been presented to any court or authority that voting machines did anything other than count votes accurately and reliably in all states."

No one from the Secretary of State’s office would agree to an interview for this story.

But in June, Secretary of State Chief Operating officer Gabriel Sterling talked to Georgia Gang contributor Martha Zoller on her radio show.

"To do the kind of attack they’re talking about doing it would take hundreds of people in thousands of locations and nobody noticing what they’re doing," said Sterling.

Two federal security agencies agreed any attack "would be difficult to conduct undetected."

Alex Halderman — the expert who said he found those vulnerabilities — challenged his critics, writing in court filings that any attack would not be discovered until it was too late. He said that would leave the state with the unenviable choice of trusting the results or re-running the election.

Halderman said the only way to make sure is for voters to read their ballot carefully before putting it into the scanner, making sure the choices printed with the QR code match their selection. But a UGA study found less than half of Georgians actually do that.

Regular audits comparing the paper ballot votes to the computer tallies would also be essential, Halderman wrote.

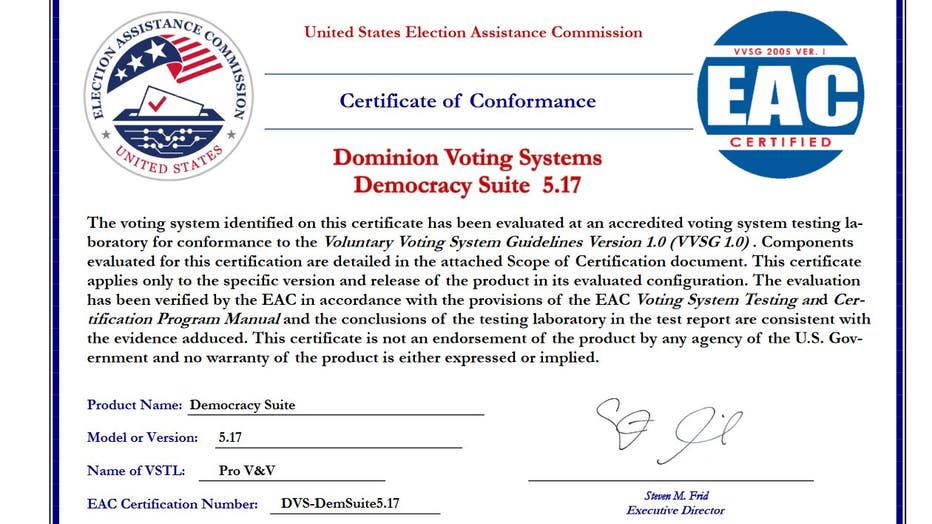

Dominion has developed an update. Georgia won't use it until after the 2024 elections.

Some want Georgia to install DVS 5.17, an updated Dominion software system certified earlier this year. But Sterling said there’s not enough time before November municipal elections to work out any bugs. They're testing it now in a handful of precincts.

"This system has never been used anywhere in America," Sterling pointed out. "I’m not about to take the state of Georgia and put it in a brand-new car and drive it around, not knowing how it works."

The plan is to install the update across Georgia after the 2024 election.

But when it comes to voting, perception is reality for many in this country. Both for those who wrongly think the last election was stolen, and those gathered in a south Georgia church wondering about the next one.