Faithless electors: Could they impact 2020 election results?

LOS ANGELES - In the wake of the 2020 presidential election, which resulted in Joe Biden being projected as the winner after narrow victories in key battleground states, many may wonder whether the results could be changed by faithless electors come January.

The United States has a total of 538 electoral votes up for grabs — equal to the number of representatives and senators the states have in Congress. Each state is guaranteed at least one seat in the House and two in the Senate.

But when voters cast a ballot on Election Day, they are not actually voting for the president. “We’re actually voting for these electors — a slate of electors chosen by the political parties,” Robert Alexander, a political science professor at Ohio Northern University and author of “Representation and the Electoral College,” said.

RELATED: Presidential debates: The history of the American political tradition

During the first week in January — approximately six weeks after the presidential elections — the acting vice president presides over a meeting of the House and Senate, where the electors’ votes are counted.

“My research over the past 5 presidential elections finds that electors are regularly lobbied to change their votes in the time between the general election is held and when they cast their votes in the Electoral College,” Alexander said. “Almost all electors were lobbied in 2008 and in 2016. Some of that lobbying is very aggressive as several electors reported getting death threats.”

The nominee who reaches 270 electoral votes is declared the winner and ultimately president of the United States.

But what happens if an elector casts a vote not in accordance with the state’s popular vote?

The term ‘faithless electors’ defined

Electors who cast a vote for someone other than their state party’s nominee are often referred to as “faithless electors.”

RELATED: Election 2020: Lawsuits filed, recount requested by Trump campaign — here’s where they stand

While states generally side with the candidate their state picks as the corresponding party’s presidential nominee, occasionally they do not.

Over the course of American election history, a total of 165 electors have cast “deviant votes” of some sort.

According to FairVote.com, a nonpartisan organization dedicated to electoral reform, 90 electors have cast deviant votes which were not ordinary votes for the presidential nominee of the elector’s political party. Meanwhile, there have been 75 instances of deviant votes for vice president.

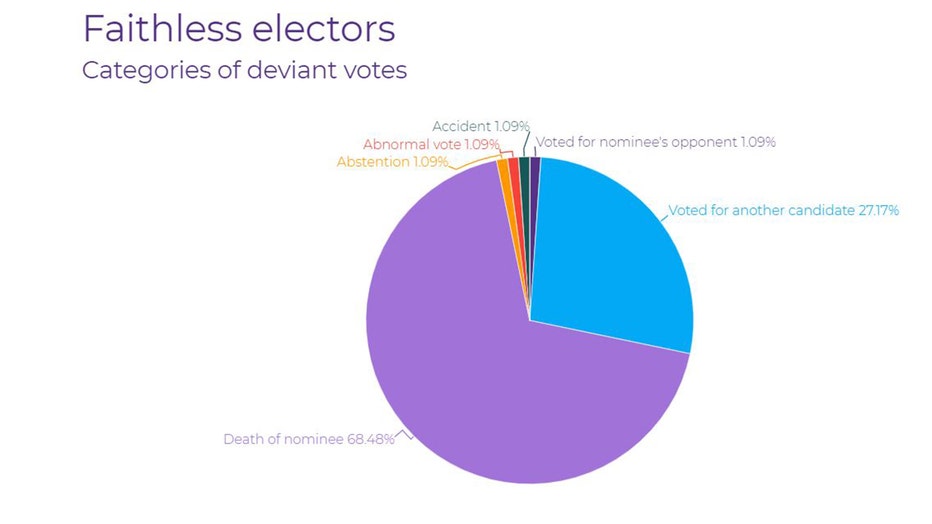

Chart highlighting categories of deviant votes among faithless electors (FairVote)

More than two-thirds of the 90 deviant presidential votes cast were for another candidate due to the death of the nominee.

Of the remaining 27 deviant votes, 24 were cast for another candidate (three were canceled or retracted due to the operation of state law).

Who was the first faithless elector?

Samuel Miles of Pennsylvania is considered the first faithless elector, in 1796. Miles, who promised to vote for Federalist candidate John Adams instead voted for Thomas Jefferson.

Since 1900, there have been 16 faithless electors who chose to vote for other presidential candidates.

RELATED: Safe harbor deadline: Here’s why Dec. 8 matters in the 2020 election

The closest Electoral College margin was in 2000, when Republican George W. Bush received 271 electoral votes compared to 266 for Democratic candidate Al Gore. One openly faithless elector, Barbara Lett Simmons from Washington, D.C., left her ballot blank.

Simmons, a longtime Democratic activist, claimed that the District was the only region that paid federal taxes but did not have a vote in Congress, the Washington Times reported.

"Taxation without representation is tyranny," Simmons said in remarks given after she cast her blank ballot, according to the Times.

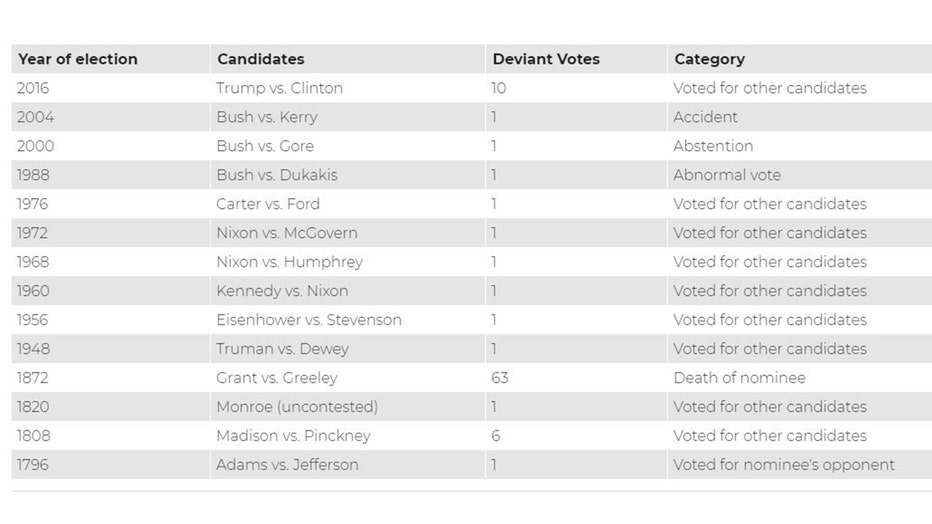

Chart showing number of deviant votes during each presidential election

But perhaps the most notable instance of faithless electors was in 2016, when 10 electors cast votes for other candidates.

“Although it did not impact the outcome, the 2016 election between Republican nominee Donald Trump and Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton included an abnormally high number of electors breaking with their political party and casting a deviant vote for President,” FairVote said.

In fact, it was the largest number of individual deviance by electors in a U.S. presidential election.

RELATED: Mitch McConnell says Trump '100% within his rights' to question election results

“There were ten electors in 2016 that tried to cast faithless votes. Seven of them were successful. Two were Republicans; the rest were Democrat,” Alexander explained. “They were unsuccessful in their attempt, but for many Americans, that is denying them the right to vote what they thought they would get back in early November.”

Of the seven faithless electors in 2016, four came from Washington, a state won by Clinton.

Three voted for former Secretary of State and Republican Colin Powell, while a fourth cast a ballot for a Native American elder named Faith Spotted Eagle.

Bret Chiafalo, who voted for Powell, said he was “ready to pay a fine of up to $1,000 if the state decides to enforce the law on faithless electors,” according to the Associated Press.

One faithless elector, David Mulinix, a Democrat from Hawaii, cast his vote for Bernie Sanders instead of Hillary Clinton.

RELATED: 2020 election: Transition challenges await Biden

Two Texas electors — Christopher Suprun and Bill Greene — voted against their party’s decided candidate. Suprun voted for John Kasich, while Greene voted for Libertarian Ron Paul.

While the 2016 electors cast a significantly higher number of deviant votes in comparison to previous election years, it also illustrates that those who voted against their state’s choice did not vote for the opposing party’s presidential candidate (i.e. voting Clinton instead of Trump and vice-versa).

Even so, deviant votes are still an effort to try and keep a president-elect from the 270 Electoral College votes needed to officially become the nation's president.

2020 Supreme Court ruling

In July 2020, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that a state may require presidential electors to follow the state’s popular vote result in the Electoral College.

A state may instruct “electors that they have no ground for reversing the vote of millions of its citizens," Justice Elena Kagan wrote in her majority opinion. "That direction accords with the Constitution — as well as with the trust of a Nation that here, We the People rule,” Kagan wrote.

SCOTUS affirmed that state laws binding electors were constitutional. This ruling left in place laws in 33 states and the District of Columbia that bind electors to vote for the popular-vote winner.

“While there are 33 states (plus DC) that have laws requiring pledges of electors, there are only 14 states that have a sanction to remove an elector if they vote contrary to expectations,” Alexander explained.

“So while most have pledges, less than half have any means of forcing electors to vote for the winner of the popular vote in their states. This amounts to 121 of the 538 electoral votes. So technically over 400 electors could go rogue if they chose to do so,” Robert said.

Could faithless electors ultimately change the 2020 election results?

While faithless electors have existed in the past, they have never been critical to the outcome, nor have they had the capacity to overturn an election.

But deviant voting among electors has become increasingly concerning in recent years, especially after 2016’s presidential election. Many wonder if a close race could be altered by faithless electors.

Biden and Trump’s projected electoral vote count stands at 290 for Biden compared to 214 for Trump, according to FOX News projections. A closer race could be a bigger concern, and it is not common for faithless electors to cast a vote for the opposing party’s candidate. In fact, it has only happened once before in American election history, according to FairVote.

“Faithless electors have never changed the outcome of a presidential election. To date, only one elector has cast a vote for the opposite party’s nominee instead of his own in a close contest. In the 1796 election - the very first contested presidential election - Samuel Miles, a Federalist elector from Pennsylvania, voted for Democratic-Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson instead of Federalist candidate John Adams,” FairVote said.

And with more states required to side with their state’s popular vote result due to this year’s Supreme Court ruling, the option is becoming increasingly difficult and looked down upon.

“It happens infrequently, but our studies have found that a number of electors actually consider that as an option more than most would think,” Alexander said. “On average, my research finds that around 10% of electors give some consideration to voting contrary to expectations.”

“Most are strong party loyalists, but they may have issues with their party's candidate or they may simply wish to use the opportunity as a platform for a pet issue. Of course, very few choose to go rogue and I expect we will see few faithless electors this year—certainly not enough to change the results of the election,” Alexander said.