Family seeks to shed light on Marine’s death, California’s lax isolation laws

Mabel Villalta (left) and Jenny Villalta (right) flank a large photograph of Edwin Villalta, a Marine who killed himself at Santa Rita Jail on Nov. 28, 2017

HAYWARD, Calif. - Edwin Villalta hanged himself at Santa Rita Jail two years ago, just after Thanksgiving.

The 29-year-old former Marine suffered from PTSD, his family said, and he committed suicide after being held alone in a cell for 17 days.

Edwin Villalta’s treatment and the events that led to his death not only haunt his family to this day, they raise serious questions about how county jails across the state care for people with mental illness and how they use isolation cells. Villalta’s story also sheds light on California’s lax laws governing the amount of time inmates can be held in solitary confinement.

“I want to lend my voice to help others,” said Edwin’s sister, Jenny Villalta, of Hayward. “We are hurting. And we don’t don’t want to turn that hurt into anger. We just don’t want anyone to go through what we went through.”

On Nov. 10, 2017, Villalta got into a solo car accident in Fremont. But when a police officer approached his car to see what happened, Villalta acted erratically. He jumped into a stranger’s empty van, stripped down to his underwear and tried to pull a gun from an officer’s holster, according to a police report. Police used a Taser to subdue him, and an officer punched him several times in the face.

Police booked Villalta on charges of stealing a vehicle and resisting arrest. When Villalta got to Santa Rita Jail in Dublin, sheriff’s deputies immediately placed him in a highly restrictive “Administrative Isolation” cell by himself.

On Nov. 28, 2017, he was pronounced dead.

An excerpt from Edwin Villalta's death report shows he was placed in isolation.

What authorities didn’t seem to take into account, his family said, was that Villalta suffered from mental health issues, which they say stemmed from his experiences in the U.S. Marines.

“He was punished for his PTSD,” Jenny Villalta said. “Police should have handled this differently.”

Jenny Villalta said her brother had not been the same since he was discharged with honors from the military in 2014. He had hearing loss, and he battled anxiety, depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after a grenade went off during a training exercise, she said. When he returned home, his mental state kept getting worse.

Villalta had been placed on three psychiatric holds prior to his Fremont arrest. He had gone to seek help at Veterans Affairs. But his sister and mother acknowledged that he only took his medication sporadically. He was distant. Evasive. He got divorced. He wasn’t paying his rent. Eventually, he took off in his car. He drove to Mexico. He dreamed of heading to Alaska.

Edwin Villalta was a computer avionics technician for the Marines.

“He didn’t think his anti-depressants were working fast enough. He started to pull away,” Jenny Villalta said. “We tried. We really tried. But it’s very hard to get an adult the help they need when they’re in denial.”

His mother, Mabel Villalta, said her son started to lack any emotional affect. He turned her away at the door on several visits. “When I saw him, his face was flat,” she said. “I didn’t know what to do.”

Villalta is one of 44 people who have died in Santa Rita Jail since 2014 – the highest jail death rate in the Bay Area. And he was one of at least 16 inmates who committed suicide during that time. 2 Investigates has previously revealed that of those suicides, at least 12 inmates, including Villalta, were kept in some form of isolation. Alameda County sheriff's officials dispute that three of these deaths happened in their custody.

While there are inmates who sometimes ask to be housed alone, many studies have concluded that, in general, keeping inmates away from other people is conducive to destructive behavior and more self-harm. UC Santa Cruz psychology professor Craig Haney, the nation's leading expert on inmate mental health, once told a U.S. Senate subcommittee, for many inmates, "solitary confinement precipitates a descent into madness."

California lax isolation laws

Villalta’s death also highlights the fact that California has no state law that places a cap on how long inmates can be held in isolation. There is also no state law addressing the criteria of who gets sent to solitary confinement. And there is no state law that mandates inmates receive any human contact during their limited free time.

In most jails and prisons across the country, the term “isolation” is not formally used any more because of its negative connotation. But criminal justice reform experts and watchdogs say the practice still exists despite any name change. To a layperson, isolation typically refers to inmates who are held in closed cells for 22 to 24 hours a day and have little human contact for days or even decades. Most solitary cells measure from 6x9 to 8x10 feet. Some have bars. Most have solid metal doors. Meals generally come through slots in the doors, as do communication with staff. Many jails now call these restrictive environments terms like “administrative separation” or “administrative management.”

The only law California has on the books is known as Title 15, which states that inmates must be let out of their cells for a total of three hours during a seven-day period. Whether or not they get to interact with people during their brief recreational time is also not spelled out under the law.

Patchwork approach to isolation policies

That means it is up to individual sheriffs and wardens to determine the rest.

“For such a progressive state like California, I find this shocking,” said Kara Janssen, an attorney with Rosen, Bien, Galvan and Grunfeld in San Francisco, whose firm filed a federal class action suit last year against Alameda County over inmate isolation and mental health care. “This is just not good enough. This lack of a higher standard sets county jails up for litigation. Jails believe they are complying with the law. But the state law does not comply with the U.S. Constitution.”

Janssen’s suit alleges that Santa Rita has “inadequate policies and procedures for monitoring prisoners in administrative isolation units, including prisoners with psychiatric disabilities,” and that deputies “failed to conduct meaningful safety checks at frequent and unpredictable times.”

An incident report by sheriff’s deputies indicates another inmate said Villalta committed suicide “because he was not receiving his appropriate medication and was depressed.”

Absent a clear law, reform efforts have come largely in a piecemeal approach by activists and lawyers.

Attorneys from Janssen’s firm, the Prison Law Office, and the Disability Rights Advocates, both in Berkeley, and the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York, to name a few, have been some of the leaders of this movement.

Their suits have forced several prisons and jails across California to enter into “consent decrees,” or legal settlements, which have ended up decreasing the number of people held in isolation, increasing recreation time, and adding stricter guidelines about who gets sent to solitary confinement. The suits almost always address inmates’ mental health care as well.

But these reforms are patchwork. And they differ from correctional facility to correctional facility.

“I would gladly be out of business suing counties over solitary confinement,” Janssen said.

Edwin Villalta had been deployed across the world. He loved to travel and visited Europe after he was discharged with honors from the military in 2014.

Isolation at Santa Rita goes by various names

In Villalta’s 2017 incident report, sheriff’s deputies noted he was housed in Housing Unit 1, an “Administrative Isolation” unit for inmates “who cannot be around anyone else due to their crime status, crime sophistication or assault history.” A separate autopsy report called his unit “Administrative Segregation,” describing his unit has a place where he had “no physical contact with other inmates.” Deputies in this unit are supposed to conduct checks every 30 minutes.

Mabel Villalta recounted her son telling her how hard it was to be alone.

“He wasn’t used to being inside all the time,” she said. “Isolation is just awful.”

Alameda County Sheriff’s spokesperson Sgt. Ray Kelly declined to comment on Villalta’s case because his family is party to Janssen’s federal class action suit.

However, Kelly said the term isolation "is inaccurate and not used in our vernacular" — despite a commander giving a presentation to the Alameda County Board of Supervisors Public Safety Committee about the jail’s use of Administrative Isolation a year ago.

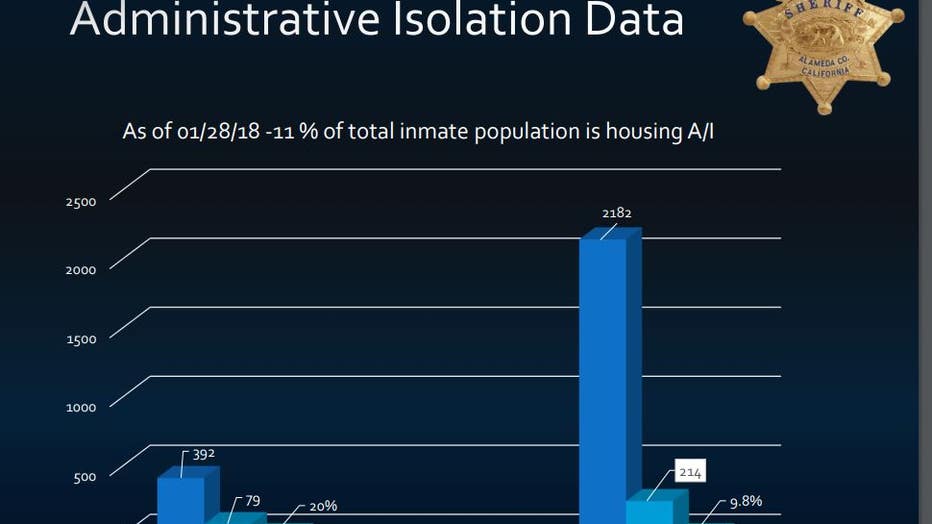

In 2018, an Alameda County Sheriff presentation noted that 11 percent of the jail's inmates were in Administrative Isolation.

In that February 2018 report, the sheriff's office said inmates are placed into "AI" if they assaulted others, needed protection or “showed complete disregard for established rules.” In that same report, the commander told the supervisors that 11 percent of the county's inmates at the time were held in Administrative Isolation.

Across the country, Solitary Watch, a prison watchdog group, noted that anything from using profanity, doing drugs, ignoring orders, or committing a violent act can land an inmate in isolation or solitary confinement. Recent studies show that people of color are over-represented in isolation and that people who suffer from mental illness are also housed there disproportionately.

Just how many people have been in Villalta’s situation has been “notoriously difficult to determine,” according to Solitary Watch. That’s because of shortcomings in data collection and the various definitions of what constitutes isolation, the group found.

Jails reform after being sued

The Alameda County jail system is far from the only one under scrutiny in California.

Don Specter from the Prison Law Office has sued Sacramento, Riverside, San Bernardino, Fresno, Santa Barbara and Santa Clara counties. And his firm is now in negotiations with Contra Costa County over the sheriff's practices regarding isolation and mental health care in the jails. He said he tried convincing about 11 or so sheriffs a few years back to adopting best practices about these issues in order to avoid lawsuits, but they “rejected my offer. They were happy with Title 15.”

So, Specter keeps suing. His efforts have resulted in a dramatic decrease in the number of inmates held in isolation.

In Santa Clara County, where there are roughly 3,300 inmates, for example, there were more than 300 people in isolation before he sued in 2015. As of August, there were just 63.

The length of stay in isolation has also decreased after Santa Clara County signed a consent decree in 2018. The average length of stay in isolation now ranges between two to five months. The inmate who brought the 2016 suit against the county, Brian Chavez, was in isolation for 1,730 days – about four years and eight months.

“However you count it, they are still a far cry from keeping hundreds of people in solitary for years,” Specter said.

In Contra Costa County, there were about 100 people in solitary earlier this year, Specter said. In June, there were only five — and the longest stay was a month, Specter said.

In an interview, Santa Clara County Sheriff Laurie Smith said she was skeptical at first of implementing many of the reforms. And even though the changes have been costly to the county – namely hiring more staff and retrofitting certain areas to maximize safety – Smith said it’s been worth it.

“I didn’t think this was going to work,” she said. “I thought if we let inmates out more often, we’d see huge increases in violence and assaults. But we haven’t.” While assaults on staff are slightly higher, she said, the number of inmate-on-inmate assaults have actually decreased.

Smith created new positions of “multi-support” deputies who work with 321 behavioral health counselors and 17 psychiatrists and psychologists to assist mentally ill inmates. Also, all Santa Clara County inmates now get a 30-day review of their housing situation every month to see if they can be reclassified to lower-level security units. And those in “administrative management,” get a chance to move out of isolation every 15 days.

Smith said she’s long felt that the state minimum standard of allowing inmates out of their cells for just three hours a week was never enough.

But she’s concerned that a state law mandating the rules of who can be put into isolation and for how long won’t allow sheriffs enough flexibility. “We have to have some latitude,” she said.

On this point, she was extremely clear.

“Let me get on my soap box,” Smith said. “Inmates who have serious mental health issues do not belong in jail.” And she said she realized that mentally ill inmates kept in isolation will likely further feel more depressed and paranoid.

“I’m glad this issue has been brought to the forefront,” she said.

Across the country, there have been a few states that have emerged as leaders in isolation reform. Prison reform advocates note that Colorado and North Dakota have started to come up with more creative alternatives to isolation and combining that with more robust mental health programs. California and New York’s prison systems, not jails, have also reduced their isolation numbers following major landmark lawsuits, Solitary Watch noted.

In the Bay Area, Smith said that Alameda and Santa Cruz county jail leaders have visited Santa Clara County as a model of best practices. And Alameda County has adopted a new policy of "Maximum Separation," where about 150 inmates who have signed contracts promising they won’t get into fights. They are then allowed more group time together than if they were housed alone.

But there is a long way to go, critics say.

“Right now, I’m not really comfortable saying that any county jail in the state is a role model,” Janssen said.

A collage of photos of Edwin Villalta when he was growing up in Hayward.

Holidays are hard at the Villalta home

Jenny Villalta said she wishes she could go back in time, to when her brother was his old self: friendly, outgoing, adventurous.

He had been deployed to farflung places like Australia and Japan. He had traveled Europe with his then-wife. Even after he returned, Jenny Villalata said her brother had been trying to get his life back on track. He had a job in an airline company and he enjoyed listening to classical music and opera.

Two years before he died, she remembers him clinging to his loved ones.

“He wanted Christmas together with his family,” his sister Jenny Villalta remembered. “He wanted things to be the way there were.”

But things will never be the same.

For now, Edwin Villalta's family must wait for the federal case to work its way through the courts. A mediation meeting is set for next month. If things can't be worked out, a trial date has been set for September 2020.

And when the Villalta family sits down at their holiday table, they will have to grapple with the gaping hole that will forever be in their lives.

“I know it’s really cliché, that you should focus on what’s really important, and that’s family,” Jenny Villalta said. “But we really, really feel it. I am teaching my kids that you never really know when someone’s last day is.”