Georgia grad student defies medical expectations, 25 years after devastating diagnosis

She survived a rare disease, now she's earning her second Master's degree

Linseigh Green of Johns Creek has spent her 25 years of life beating all odds. Her parents knew nothing about Necrotizing Enterocolitis when she was diagnosed at two weeks old. Linseigh says she's one of the first NEC survivors in the world to get the chance to share their story at medical conferences.

ATLANTA - Linseigh Green of Johns Creek, Georgia, has spent 25 years defying the odds, a survivor of a harrowing intestinal disease known as Necrotizing Enterocolitis, or NEC.

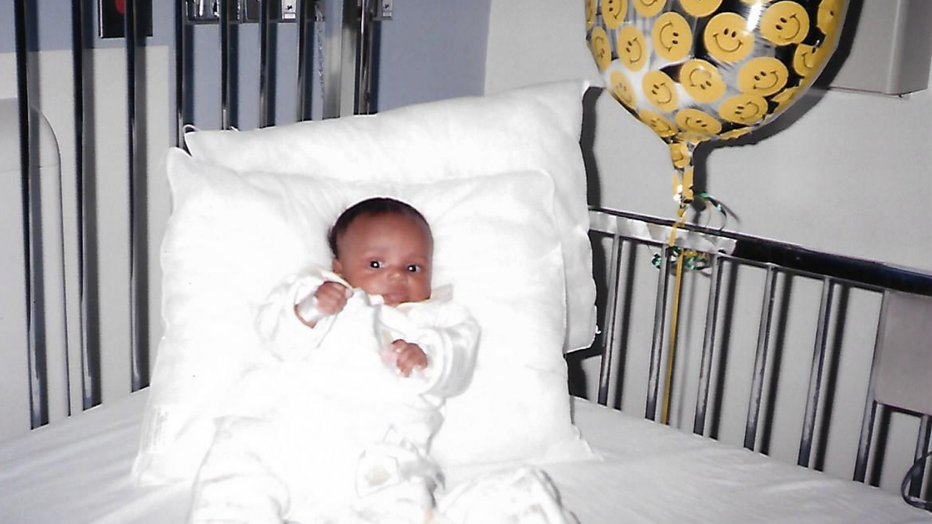

"I was diagnosed with NEC when I was two weeks old," Green said. "But, from the moment that I was born, I was sick. I went straight from the delivery room to the NICU."

Dr. John Bleacher, a pediatric surgeon who retired earlier this year from Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, was Green's surgeon in 1997.

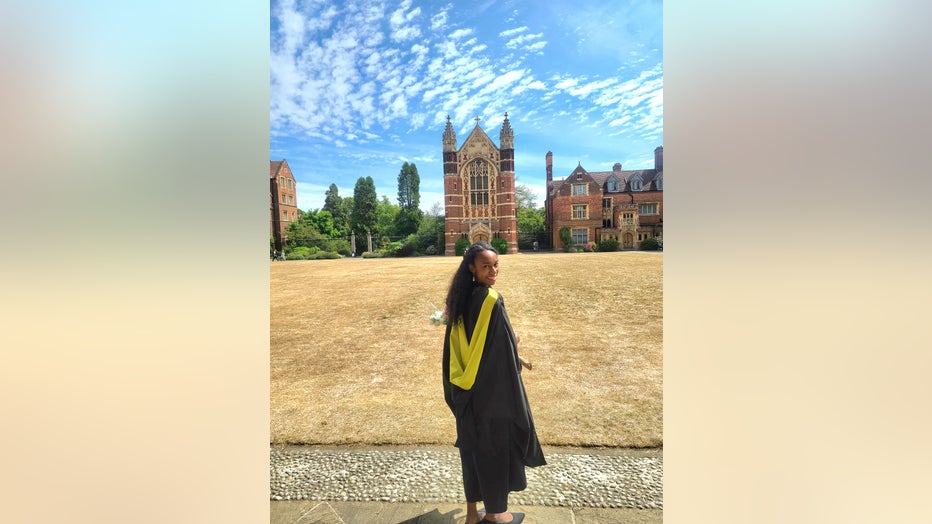

Linseigh Green poses in her graduation gown after earning her master's degree at the University of Cambridge. (Linseigh Green)

Dr. Bleacher said NEC typically affects infants born premature or medically-fragile, and it is difficult to treat.

"One of the devastating things about it is that the overall mortality rate for babies that get this is about 30 to 40%," he said.

Lindseigh Green after her first surgery in 1997.

Although it is still not clear what causes NEC or how to prevent it, Dr. Bleacher said NEC often occurs in babies whose digestive and immune systems are still developing, who may not be getting enough blood flow to their gut.

That can allow dangerous bacteria to move in and take over, releasing toxins that destroy the intestinal tissue.

Linseigh Green in the late 1990s.

"What we notice is that a baby will be doing fine, being fed, and then all of a sudden her abdomen will become very distended," Bleacher said. "The first line of treatment is to stop feeds, let the intestines rest, start broad spectrum antibiotics to treat infection and just support the baby. If the tissues are dying, then antibiotics are not going to help."

For Green, Bleacher performed two surgeries, the first to remove her dead intestinal tissue. Once she had had a chance to heal, he performed another to reconnect her intestines.

Linseigh Green after her second surgery at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta.

Early on, Green said, her parents were very open about her medical challenges.

"I remember, even as a toddler, I had this little photo album of my NICU journey," she said. "So, my parents would sit me down and show it to me, and I was horrified because it didn't look very cute and perfect. I saw my colostomy bag and my stoma, and I saw a ventilation tube up my nose."

Green grew up with a scar on her belly and long-term complications of NEC.

"Even though I made good grades, I was very slow, pacing was very slow," she said. "I'd often have to be put out in the hallway or sit in the back of the classroom to finish assignments while the rest of the class moved on."

She struggled to keep up her weight.

"I had a lot of difficulty eating a normal amount of food in one sitting," Green remembered.

In high school, she was hospitalized for severe intestinal pain.

But it was not until Green graduated from Marist in Atlanta, and went to college at NYU, that she discovered the non-profit NEC Society, where she began to hear how others were affected by NEC.

Linseigh Green at the NYU graduation at Yankee Stadium in 2019

"These children, a lot of them are children, they're struggling with cerebral palsy, they're non-verbal, they rely on tube feeding," she said. "When I found out the different ways that my life could have turned out, it was just a lot to process. And, I felt both gratitude, but also I felt kind of shaken because I realized, 'Oh my gosh, that could have been me, things could have turned out so differently for me.'"

Linseigh Green at Cambridge University, where she earned a master's degree.

While studying for her master's degree at the University of Cambridge, Green said she struggled with partial paralysis, a speech impediment, and a tic that causes her eyes to close, which she has been told may be neurological long term complications of NEC.

Recently, she said she was diagnosed with Functional Neurological Disorder.

"Basically, I somehow made it through Cambridge and graduated with top honors while having cognitive dysfunction," she said.

Dr. Bleacher said seeing Green thriving today gives him "goosebumps."

Linseigh Green stands of Cambridge Hill in Cambridge, England.

"To see her as a successful, thriving young lady is very gratifying," he said.

Linseigh Green is now back in England, working on her second master's degree, this time in immersive storytelling, beginning with her own story.

Linseigh Green is awarded her master's degree at Cambridge University in 2022.

She is one of the first and only NEC survivors to speak at medical conferences and promote awareness about the need for funding and research to better understand Necrotizing Enterocolitis.

"One mom told me, 'You know, my son can't speak because he had NEC, and you have a voice; so, every single time that you speak up, I feel like you're speaking for my son,'" Green said.