Great white shark, 10-feet-long and weighing 700 pounds, 'pings' off coast of Georgia

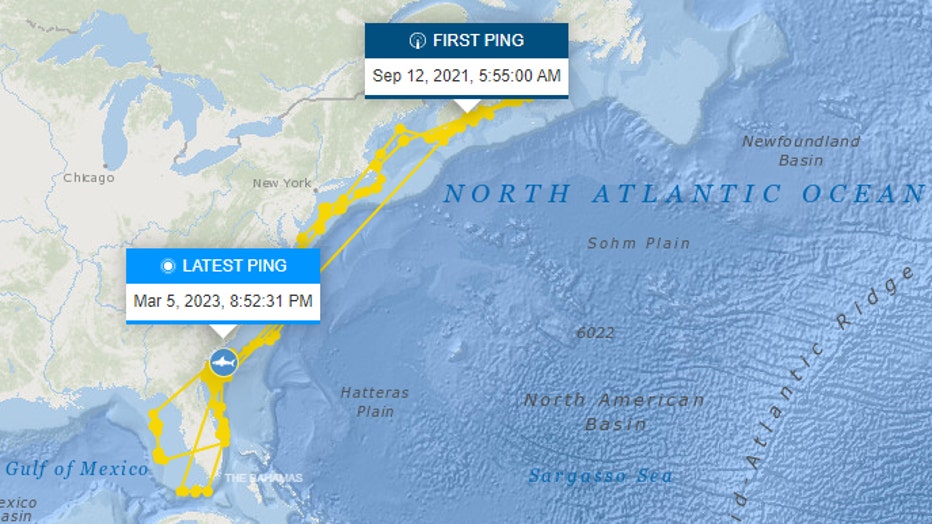

This image from OCEARCH shows great white shark Hali being tagged off the coast of Nova Scotia on Sept. 12, 2021. (OCEARCH)

Scientists are tracking a 10-foot-long great white shark weighing about 700 pounds off the coast of Georgia.

Hali, a tagged juvenile female great white shark, "pinged" about 60 miles off the coast of Tybee Island this past weekend, according to OCEARCH.

Hali was originally tagged during the research organization’s Expedition Nova Scotia 2021. She is named to honor the people of Halifax, Nova Scotia as a way to thank them for their hospitality.

However, she was not one just to stay in place, as most sharks migrate. The research group has tracked her going up and down the coast numerous times and even making it to the west coast of Florida.

This image from OCEARCH.org shows the track of great white shark Hali from when she was first tagged off the coast of Nova Scotia on Sept. 12, 2021 to near Tybee Island on March 5, 2023. (OCEARCH.org)

Hali appears to linger off the coast of Georgia in February, March, and April. She pinged about 40 miles off the coast of Amelia Island on Feb. 12 and moved north, meandering just off the Georgia coast for the last month.

The past two years, Hali appears to have called the waters off the coast of Georgia her spring home. She will likely head back north to the New England coast and Nova Scotia for the summer and early fall before shooting back down the coast to Florida for the winter months.

Hali can be tracked online through the OCEARCH website.

She is the 75th tagged shark in OCEARCH’s Northwest Atlantic White Shark Study.

How are great white sharks tracked in the Atlantic Ocean?

Research first need to capture the sharks safely. To do that, OCEARCH crews use hand lines to guide the shark onto a submerged platform, which is then raised out of the water. Once the shark is restrained, researchers use hoses to ensure the shark received a continuous flow of fresh seawater over the gills.

The science teams will then take samples and begin the tagging process. A SPOT Tag, or Smart Positioning and Temperature tag, will be attached to the dorsal fin.

After the process, the shark is released and begins swimming strongly within two to four hours.

The tag will not "ping" until the shark fin has been out of the water for 90 seconds. It then sends its signals to a satellite, which will record the data.

The data from there is them posted to the OCEARCH website, which is shared with the public and other research organizations.

Each tag is designed to last about five years before harmlessly falling off.

While the tag may cause some level of discomfort, OCEARCH says there is no evidence it impacts behavior or survival after it is released. There is also no evidence it causes any damage to the shark, researchers say.

How big do great white sharks get?

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says at birth, a great white shark pup is typically around five feet long.

They can grow to be about 20 feet long and weighing more than 4,000 pounds.

Male sharks mature at around 26 years and females at about 33 years.

New research suggests sharks can live up to or longer than 70 years.

What do great white sharks eat?

Sharks less than 10 feet typically eat bottom fish, smaller sharks and rays, and schooling fish and squids.

Large sharks transition to eating seals and sea lions and sometimes dead whales.

Hali likely just began hunting for larger prey around the time she was tagged.

Contrary to popular belief and popular movies, sharks do not typically enjoy the taste of human flesh and will often let go once they realize it is not their typical prey.

What is OCEARCH?

OCEARCH is a global non-profit organization dedicated to the collection and dispersal of research data from the ocean’s giant sea life. Since 2007, it has assembled a coalition of more than 200 scientists, researchers, veterinarians, and volunteers in that goal.

They also offer STEM programs and educational resources for the classroom.

So far, they have conducted 44 expeditions and tagging 437 animals, but do not worry, they have a big boat.

All of its tagged animals can be tracked at website at OCEARCH.org.

This story is being reported out of Atlanta