He boasted about breaching election computers, forever linking Fulton and Coffee County

A picture Scott Hall texted on his way to the Coffee County Elections Office January 7, 2021. This was obtained through discovery in a civil lawsuit filed by a non-profit.

DOUGLAS, Ga. - The Fulton County election racketeering case implicated 19 people, but four are accused of committing crimes far from Atlanta.

It's a place more than 200 miles from Fulton County. A place that couldn’t be more different.

Coffee County is largely rural, majority white, with 70% overall voting for Donald Trump to be re-elected in 2020.

In Fulton County, roughly the same — 73% — preferred Joe Biden in the last election.

Coffee County has 43,000 residents. Unless they're related to one, chances are no one in North Georgia has thought much about this rural community in South Georgia.

Despite their differences, the two will be forever connected because of the historic indictment of former president Trump and his supporters. But it’s likely that Coffee County would have remained unnoticed by District Attorney Fani Willis if were not for a nonprofit election security group, and a future defendant who felt the need to brag.

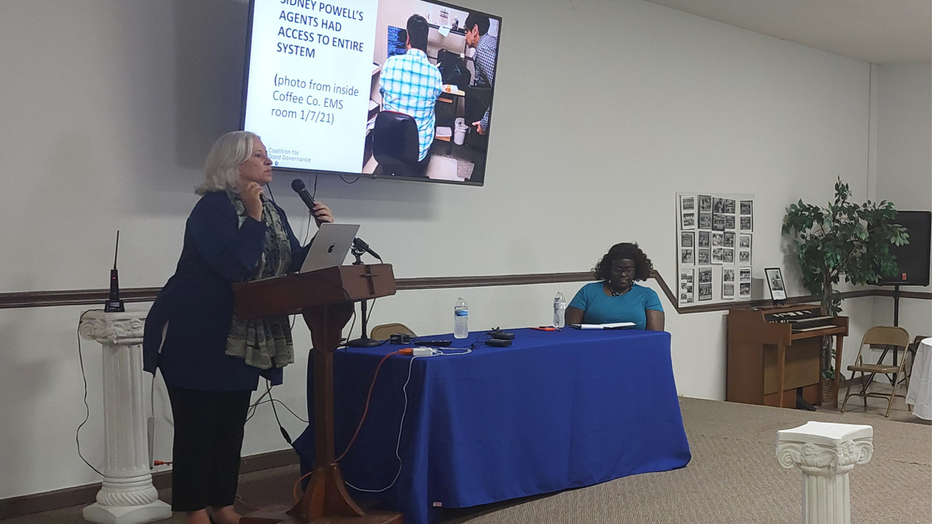

"We knew it was important," said Marilyn Marks, executive director for the Coalition for Good Governance. "But we see now that D.A. Willis also saw what an important part it was in this massive conspiracy."

Marilyn Marks shares her group's findings at a community event Saturday in Coffee County.

Long before the 2020 election, Marks’ organization sued the state of Georgia and Brad Raffensperger, concerned about the security of computerized voting machines.

It's their lawsuit that led to all Georgians now printing out a paper ballot that the voter must hand feed into the scanner. They want the state to eventually get rid of the touchscreens altogether.

WHO ARE THE 19 PEOPLE INDICTED IN FULTON COUNTY'S ELECTION INTERFERENCE CASE?

According to court filings, on March 7, 2021, Atlanta bondsman Scott Hall cold-called Marks, demanding she give him any evidence she had that would help him prove the machines were manipulated to wrongly steal the state from Trump.

But the enemy of your enemy is not necessarily your friend. Marks insists her group is non-political. And they had no evidence proving anything went wrong in the 2020 count.

"And at that point my first instinct was to slam the phone down," she recounted for the FOX 5 I-Team. "My second instinct was to go into sweet little old lady mode and hit the record button."

Georgia election indictment: Video links Fulton, Coffee

The Fulton County election racketeering case implicated 19 people, but some are accused of committing their crimes far from Atlanta. It’s actually a place more than 200 miles from Fulton County. A place FOX 5 I-Team reporter Randy Travis says became part of the investigation through a non-profit’s determination and some ill-timed bravado.

Here’s what Hall says on the recording about a visit he took to Coffee County:

"I went down there. We scanned every freaking ballot."

"They said we give you permission. Go for it. So they went in there and imaged every hard drive of every piece of equipment."

But neither the state of Georgia nor Dominion had given anyone permission to access their voting systems. In fact, a warning mailed out by the Secretary of State’s Office two months earlier warned against providing "copies of software..."

"Information that could harm the security of election equipment cannot be provided," the statement stressed, highlighting the word.

Scott Hall had just admitted being part of a group that copied Dominion Voting software from the Coffee County Elections Office.

"Now I was in triple shock and I didn't know what to think," Marks remembered.

She said she alerted the state, but no one seemed interested. Not knowing exactly when the copying was done, Marks' group filed open records requests for three months of Elections Office surveillance video which, according to court filings, Coffee County denied having.

Finally, a year ago the county turned over the videos. And they were a gold mine.

"I think the videos just make it all so very real," Marks agreed.

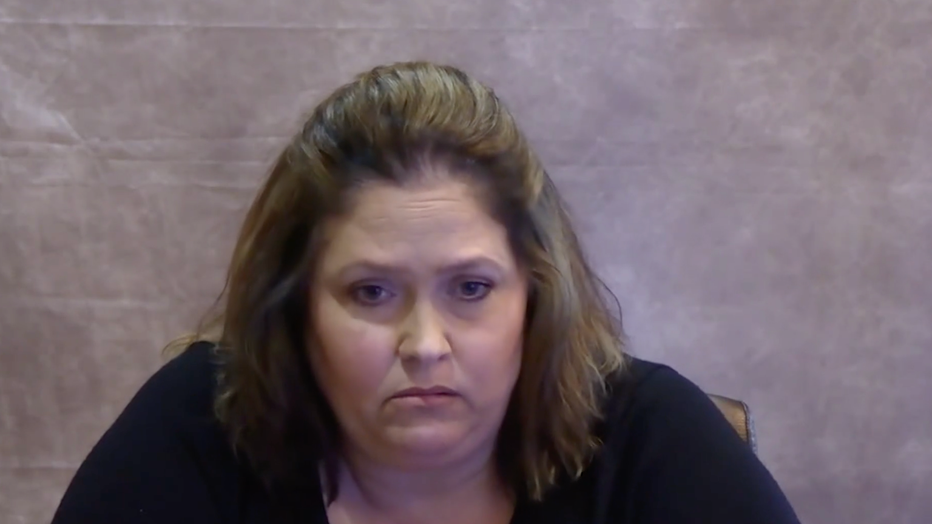

Cathy Latham was deposed for a civil suit August 8, 2022. She would be indicted one year later.

They show Hall, Coffee County GOP Chair Cathy Latham and Elections Supervisor Misty Hampton welcoming representatives of an Atlanta cyber company that was paid $26,220 by Trump ally Sidney Powell to copy Dominion software.

Last week, Hall, Latham, Hampton and Powell were indicted on the same seven counts of racketeering, computer theft, computer fraud and conspiracy to defraud the state.

Before their arrests, Latham and Hampton were deposed by the Coalition for Good Governance as part of their civil lawsuit against the state.

Latham, a retired high school economics teacher, refused to answer many of the questions from Coalition attorney David Cross.

Cross: "Have you ever had any communications with Rudy Giuliani?"

Cross: "Fifth Amendment."

In their court filings, the Coalition accused Latham of lying about the extent of her involvement. Like this exchange:

Cross: "Did you see Scott Hall?

Cross: "No, Scott came from outside. And he and I talked outside, and I was glad to have met him. And I left."

But when the plaintiffs later obtained the surveillance video, it showed Latham inside the elections office throughout the day, warmly interacting with the very people she claimed not to remember.

Cross: "Do you believe you have committed any crime?"

Latham: "Fifth Amendment."

Misty Hampton was later fired from Coffee County, accused of falsifying time sheets. The GBI is still investigating the circumstances surrounding the voting system data breach.

Elections supervisor Hampton testified that she was told the outside cyber experts were there to figure out why a scanner wasn't working properly.

Hampton: "I didn't know that... I didn't know that it was software that there were copying."

Attorney: What did you think they were copying?"

Hampton: "I’m not a computer expert, so I really don’t know."

And then later this exchange:

Attorney: "Did you ever get any feedback from anyone based upon their analysis of the copies of Coffee County's software that was made on January 7?"

Hampton: "No sir."

Attorney: "Did you ask for any?"

Hampton: "I don't recall."

The plaintiffs fear that the sharing of such data with others could help so-called "bad actors" come up with ways to compromise future voting systems, in essence creating the very problem Scott Hall told Marilyn Marks he was trying to prove in the first place.