Lawyers: Juror was biased, man's execution should be halted

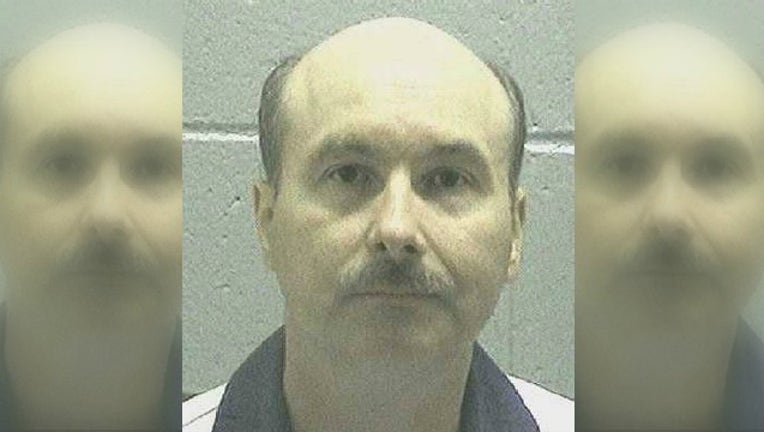

Photo courtesy of Georgia Department of Corrections

ATLANTA (AP) — The execution of a Georgia death row inmate convicted of killing his father-in-law following a custody fight over his young son should be halted because a juror lied about her own custody battle and messy divorces — and then persuaded fellow jurors to vote for a death sentence, his attorneys argue.

No one disputes that William Sallie killed John Lee Moore in March 1990, but he has been unable to present evidence of juror bias that should entitle him to a new trial because he missed a filing deadline by eight days at a time when he didn't have a lawyer, his lawyers have said in court filings.

Sallie, 50, is scheduled to be put to death Tuesday. His first conviction and death sentence were overturned because his trial lawyer was at the same time a law clerk for judges in the circuit where the trial was held.

During his second trial, in 2001, the woman eventually chosen as a juror lied during jury selection and failed to disclose domestic violence, messy divorces and a child custody battle that were "bizarrely similar" to Sallie's case, his lawyers said. She later bragged to his attorneys' investigator that she convinced her divided peers to vote unanimously for death.

Sallie had abused his wife, who was living with her parents in rural south Georgia in March 1990 after filing for divorce, according to a Georgia Supreme Court summary of the case. The two fought over their son, with custody ultimately going to Sallie's wife.

After breaking into his in-laws' house early one morning, Sallie shot John and Linda Moore in their bedroom. John Moore died from his injuries.

Death sentences in Georgia are automatically appealed. Once that appeal is complete, post-conviction proceedings involving petitions challenging the legality of the conviction and/or the sentence are typically filed in state court and, subsequently, federal court.

There's no time limit to file a post-conviction petition in Georgia courts. There's a one-year limit after the direct appeal is complete to file a post-conviction petition in federal court, but that clock pauses once a state petition is filed and stays paused until appeals on the state petition are completed.

Sallie filed his state post-conviction petition on his own a year and eight days after his direct appeal was complete. Since it was more than a year after the direct appeal ended, the clock wasn't paused on the federal filing deadline and it expired.

Georgia and Alabama are the only two states that don't guarantee an attorney for state post-conviction proceedings, according to the American Bar Association. Sallie's lack of an attorney is the reason he failed to file his state petition in time to keep the federal petition deadline from expiring, his lawyers argue.

Lawyers who later stepped in to handle Sallie's state post-conviction petition were aware that a female juror had started an affair with a married male juror while they were sequestered during the trial. But they failed to look into the woman's history, where they would have discovered her bias and ineligibility to be a juror, Sallie's lawyers say.

Sallie's lawyers uncovered the alleged bias in 2012. They tried to raise the issue in federal post-conviction petitions, saying his earlier lawyers were ineffective, but a federal court and federal appeals court have ruled the evidence can't be considered because the deadline to file the federal petition passed in 2004 and it wasn't raised in the state post-conviction proceedings.

Now they want the U.S. Supreme Court to halt his execution. They argue that the high court's ruling in a pending Texas case with ineffective counsel issues could remove the procedural bars that are keeping the lower federal courts from considering their juror-bias claims. But that decision could come after Tuesday — too late for Sallie.

Attorneys for the state have argued the Texas case isn't similar enough that its outcome would affect Sallie, particularly because that case doesn't involve a federal petition that wasn't filed on time. Furthermore, they argue, even if the issues were identical, the federal appeals court in Atlanta is bound by its own precedent — which doesn't allow such an extraordinary admission of the procedurally barred evidence — and not by the future possibility of new precedent from the Supreme Court.