Meet some of Forsyth County's reconcilers who spread love in a county that became infamous for hate

BHM: Changes to Forsyth County since the Civil War

Not long after the Civil War, hundreds of Black families lived and thrived in Forsyth County, owning their own land and creating wealth. But in 1912, that development came to a halt after a white woman's death and the Black population was forced to virtually disappear. Impacts from the expulsion are still visible today, but there are some of the ways people are trying to help Forsyth County reconcile.

FORSYTH COUNTY, Ga. - Not long after the civil war, hundreds of Black families lived and thrived in Forsyth County, owning their own land and creating wealth. In 1912, after a white woman's death, that development came to a halt and the Black population was forced to virtually disappear.

Impacts from the expulsion are still visible today, but some of the ways people are working toward reconciliation including a growing scholarship and networking events.

"Back in 1987, Oprah Winfrey came here and did her first road show in Forsyth County, Georgia, and she called Forsyth County, Georgia, 'the most racist county in America,'" Durwood Snead said. "But our vision is that this county would be known all over the world as the county of love."

Several people in Georgia’s richest county will tell you the road to reconciliation is less traveled.

"You go into a room, and you may see only one or two other Black people in the room of 100 people," Daniel Blackman said.

The people who are willing to make that lesser traveled trek are seeing their efforts "pay off."

In the early 1900s-- there were several race massacres across the country. Forsyth’s started in what was once known as "Oscarville."

Snead, who has lived in Forsyth County for 30 years, hadn't heard about Oscarville until a few years ago, as he saw an old sign while out for a drive.

"I Googled it that night and learned this crazy story of things that happened in 1912," he said.

At the time, development in Forsyth's Black community was booming.

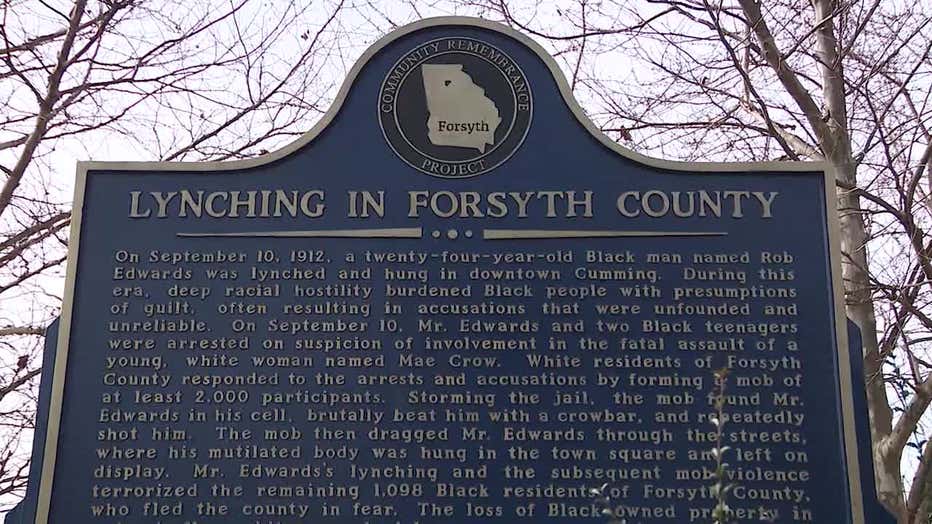

"An 18-year-old white girl was raped and brutalized one night, and they found her body the next day," Snead said. "Then two boys, 16- and 17-year-old, were tried for the crime and convicted and publicly hung. In Cumming."

Families feared for their lives and moved to other counties or even states.

Like Chase Evans' family. His great grandmother was one of those "expelled" people.

"She was only three years old," Evans said.

His ancestors sought refuge in Northwest Georgia, often attending services at Pleasant Hill Baptist church to this day. They never returned to Forsyth, except for a random car accident in the 1970s that sent Evans' aunts and uncles to a county hospital.

"They said 'we stabilized you enough to get out now. You need to be out of here by sundown.'"

Today, he works for Florida's water compliance-- thanks, in large part, to the Forsyth descendants scholarship.

"They help you, you know, this is how you format your resume and this is how you do an interview," Evans said.

"People have to prove descendancy and they have to write an essay on the journey of their family after expulsion," Snead said.

Snead is one of the scholarship’s founders, a dedicated "reconciler" and former pastor. He started giving descendants what he believes they're due with reassurance from strangers who would one day become his friends, like Jonathan Hall.

He holds public events for Black men new to the county. They share resources and network.

"It is critical that we meet in a public place so other Blacks in community to know I’m not the only one here," Hall said.

Daniel Blackman founded "The Longest Table." It's An initiative that fosters conversations that spark change.

"I don't think there's anyone whether they agree with what happened or not would want a part of their lineage robbed," he said.

He is also the first Black man to run for a public office in the county and spearheaded the movement to place a historical placard where the Black men were lynched in 1912. He's part of the force that cleared a Black cemetery filled with people who thrived in this county before the racial tension.

"We owe it to the people behind us to remember them and fight for the people who never got a chance to experience the opportunities they tried to build," he said. "What would it mean for those families who bought a property for $2,000 and now it's worth $2 or $3 million."

These reconcilers say their efforts are not atonement, they’re not reparations, they’re efforts are just more steps on the century plus long road healing.

"If this could happen in Forsyth County, Georgia-- going from being the most racist county in the country to a county of love, it could happen anywhere," Snead said.

The Source: This article is based on original reporting by FOX 5's Alex Whittler.