Program helps post 9/11 combat veterans heal from hidden scars of war

ATLANTA - Garrett Cathcart knew back in elementary school he wanted to attend the U.S. Military Academy.

Garrett Cathcart served three combat tours as a young U.S. Army officer. Six years after leaving the military, Cathcart is finally comfortable talking about his memories of combat. (Garrett Cathcart / FOX 5 Atlanta)

He was at West Point in 2001 when the Twin Towers fell. A year after Cathcart graduated in 2004, the now 38-year old found himself in Iraq, leading a platoon of soldiers.

In combat, Cathcart experienced the greatest highs and lows of his life.

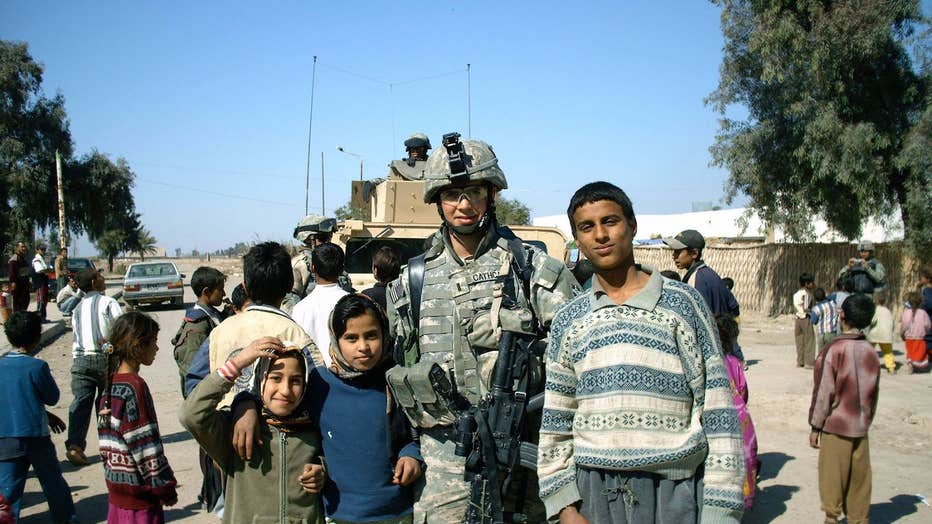

Garrett Cathcart in Iraq.

"You have purpose; you always have a mission," Cathcart says. "You're worried about what's in front of you the next hour, the next day."

Six years after he left the Army, Cathcart's Atlanta loft is full of memories of service.

There is his Cavalry Stetson sitting on top of his bookshelf.

There is a photo of the day Cathcart pinned the hard-earned Army Army Ranger tab on his twin brother.

And, there's another photo of Cathcart with his West Point roommate and best friend, David Fraser.

Garrett Cathcart poses with his West Point best friend David Fraser, who was killed in action in Iraq in 2006. (Garrett Cathcart)

"He actually was killed in action on his last day in Iraq," Cathcart says. "That photo was taken right before we deployed to Iraq our first time."

Cathcart served three combat tours in his nine years in the Army, two in Iraq, another in Afghanistan.

On his first deployment, serving as a platoon leader during 2006 military surge in Iraq, Cathcart lost his commanding officer and four soldiers.

Each time, Cathcart says, they would pause briefly for a memorial service for the fallen soldier.

"You salute the rifle, and the dog tags, and the helmet," Cathcart remembers. "But, the next day you're back out, operating and going on patrols and raids. I knew, even then, back in '06, no one was taking time to process what was happening. You can't. You've got to go back out and keep fighting, right?"

Veterans find healing

'Headstrong' program helps post-September 11th veterans and their families find healing

Simone Sobel, a clinical social worker and psychotherapist in Atlanta who specializes in trauma and PTSD, says that constant cycle can leave combat veterans emotionally numb, unable to come to terms with the traumas they are experiencing.

"It's very easy for them to fall through the cracks," Sobel says. "They're stoic, and there is the stigma. They're isolated."

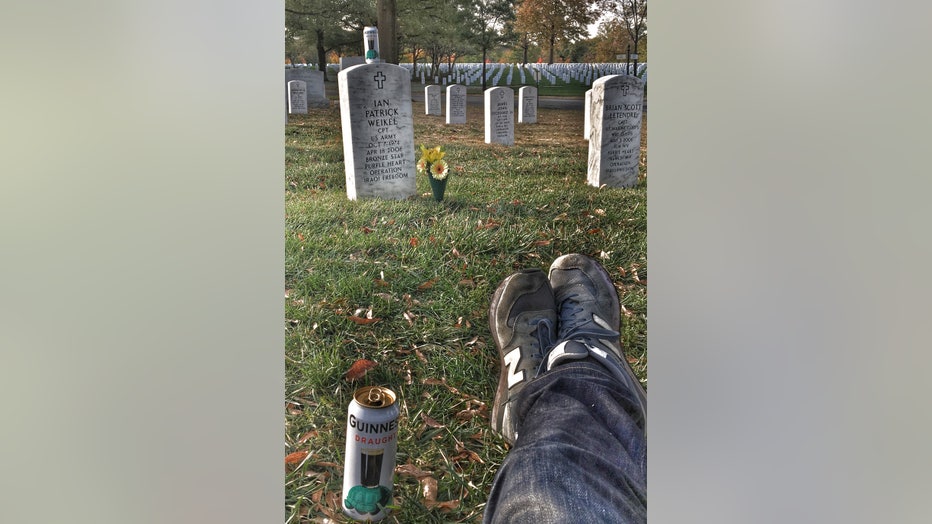

Garrett Cathcart sits beside a friend's grave at Arlington National Cemetery.

Cathcart says he kept his focus on his next deployment.

He has never been diagnosed with PTSD or depression.

Still, Cathcart acknowledges, he could not talk about his combat experiences for years.

"It's so traumatic," he says. "Why would you ever bring it up? It's the same mindset: I'll get through this. I'll white-knuckle it. But you get to the point where that's not enough, you've got to talk to somebody."

Sobel wants to be that somebody.

Garrett Cathcart poses with children in Iraq in 2006.

She is a provider for Headstrong, a national nonprofit that focuses on military trauma and military sexual trauma.

Headstrong offers free mental health treatment to post-9/11 combat vets and their families.

"We used to think that trauma was untreatable, because we were doing a lot of talking, and people were spending years in therapy just talking." Sobel says. "The type of therapy we do in trauma is really not based in a whole lot of talking. It's much more of a brain-based therapy, where we do lots of specific memory-based processing. So it can work quite quickly."

Veterans can sign up for the program on Headstrong's website.

Sobel says they will get a response within 48 hours, connecting them to providers in their area.

Garrett Cathcart left the Army in 2013. He now works for a military-focused nonprofit in Atlanta.

Treatment, she says, can be tailored to the veteran's needs.

Garrett Cathcart recently signed up for his first counseling session. He is hoping other combat veterans will follow his lead.

"If you're in the best shape of your life, but you can't focus, and you can't sleep, then you're not good, man," Cathcart says. "So you've got iron it out. Go fix it, right? But, I tell you, there is a great life out there, and it's one you've earned, and folks want to give it to you. But you have to go grab it. You have to get off the couch and go get it."