Seeing Private Hall: Army officially remembers only lynching victim on military installation

Army officially remembers only lynching victim on military installation

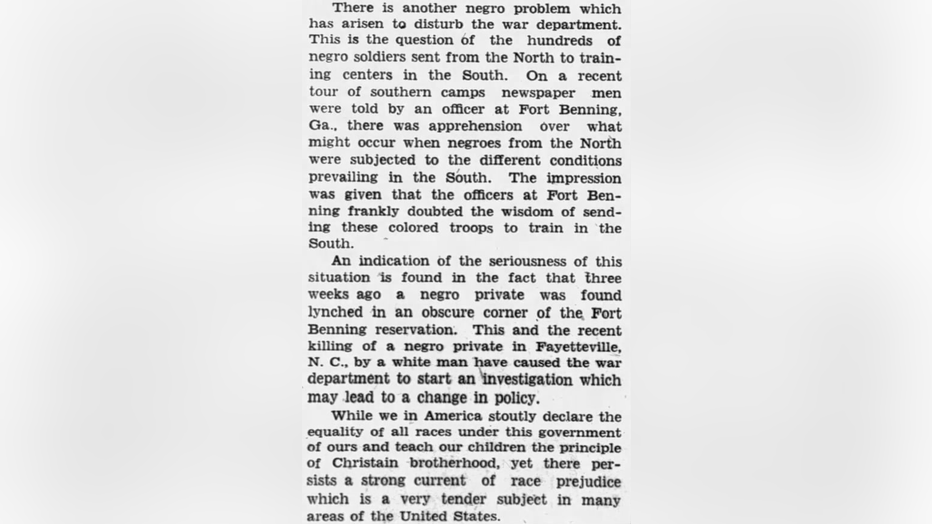

For 80 years, thousands of soldiers have passed through Fort Benning, unaware of its tragic place in American history: the site of what’s believed to be the only lynching on a U.S. military installation.

FORT BENNING, Ga. - For 80 years, thousands of soldiers have passed through Fort Benning, unaware of its tragic place in American history: the site of what’s believed to be the only lynching on a U.S. military installation.

On Tuesday, the Army plans to make sure future soldiers will know.

Dignitaries will gather near the spot where Private Felix Hall was last seen alive. A plaque will be unveiled. His story will finally be told there.

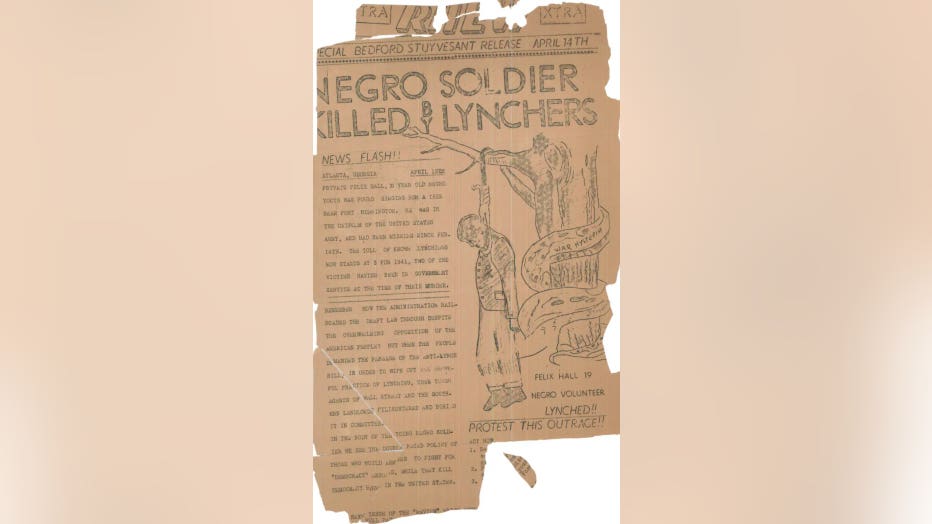

A 1941 flyer spread the news about the lynching of private Felix Hall at Fort Benning, GA.

"Horrific … inhumane … it’s difficult to talk about … very disturbing," said Col. Michael Tremblay, chief of staff for the Maneuver Center of Excellence at Fort Benning.

So why now?

"To have a clear-eyed view of history," Tremblay answered. "Both the good and the bad at Fort Benning."

Private Hall's decomposing body was found tied to a sapling somewhere in this ravine.

Eighty years ago the US Army was still segregated, Black soldiers housed and fed in the so-called colored section of Fort Benning. Thousands of volunteers were pouring in to join the 24th Infantry Regiment in 1941. They would be known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

Pearl Harbor was still months away.

One of those Black soldiers, 19-year-old Private Felix Hall, was assigned to work at the sawmill located on Fort Benning property. According to the FBI case file, on Feb. 12, 1941, Hall knocked off work and told his buddies he was heading to the PX. Hall never made it.

Now a museum, the Colored Post Exchange still stands today at Fort Benning. Private Hall told friends he was heading here on February 12, 1941 but never made it.

Six weeks later a platoon of engineers training in the woods came upon Hall’s decomposing body tied to a sapling in a ravine. A rope tied around his neck. His feet were bound with baling wire. His hands were also tied.

Hall had been strung up still alive.

According to the FBI investigation, a pile of dirt under Hall’s body indicated he had tried unsuccessfully to dig out of the side of the ravine with his feet so he might have something to stand on.

There are no surviving photographs of Felix Hall when he was alive. Only the crime scene photos showing how he died.

"Now the people that did this, I feel real sorry for them because of this," Hall’s surviving cousin James Fenderson, 85, told the FOX 5 I-Team. "You can take something that you can’t give back. That’s the worst thing in the world."

James Fenderson, 85, is one of the few relatives who remember what happened to Felix Hall.

So who murdered Felix Hall? According to the FBI case file, investigators decided the crime had to involve multiple people.

They focused on a pair of white sergeants who lived along the route Hall would have taken to get to the Post Exchange. They even matched the rope used in the lynching to rope found in the house the two suspects shared.

But that rope was commonly used all over Fort Benning. One of the sergeants denied his involvement. The other had already been shipped out. The case was ultimately closed. No one was ever arrested for what would be the only lynching on a U.S. military installation.

"Some white people did this to Felix," said Fenderson. "Were jealous of him. They didn’t like him for some reason."

Black-owned newspapers across the country -- and some Northern papers like the Burlington Vermont Free Press -- blamed Hall's murder on white soldiers unhappy with Black soldiers joining the Army.

Hall’s murder at the time generated a tremendous amount of coverage in Black-owned newspapers.

His FBI file includes transcribed letters written by people urging the lynching "not be passed over and forgotten."

But a paranoid FBI chalked up much of that response to "Communists" who "had interested themselves in this case."

It would take 80 years for the military to finally acknowledge the crime. To finally start seeing Private Hall.

"It was done in the dark, but it’s finally come to the light," agreed another of Hall’s relatives, Lillian Fenderson-Lykes.

Why the delay?

"We just weren’t aware," admitted Col. Tremblay.

Thousands of soldiers passed through Fort Benning over the last 80 years not knowing its dubious place in history. "We just weren't aware," admitted Col. Michael Tremblay.

Not until 2016, when the Washington Post reported on the long-forgotten tragedy.

The story attracted the attention of Georgia Congressman Sanford Bishop. When Major General Patrick Donahoe took command at Fort Benning, Bishop asked him to correct the record.

Tell the truth. Admit something unforgivable happened here.

"What we don’t want to do is bury that and kind of turn away from things that we’ve done," said Col. Tremblay. "Quite frankly it’s the right thing to do."

A sign marks the spot at Fort Benning where Private Hall's body was found. Another marker will be unveiled Tuesday near where he was last seen alive.

Hall grew up in Millbrook, AL, about two hours from Fort Benning. Few people today remember him there or even know his reluctant place in history.

But just down the road in Montgomery, his name is inscribed in the National Memorial For Peace and Justice along with the other 4400 lynching victims in the US.

On Tuesday, a new marker will remember what happened. This time, where it happened.

WATCH: FOX 5 Atlanta live news coverage

_____

Sign up for FOX 5 email alerts

Download the FOX 5 Atlanta app for breaking news and weather alerts.