Used for both good and evil, golden gun finally comes home

Before it was gold plated, this .38 caliber revolver belonged to the first black APD officer killed in the line of duty.

DOUGLASVILLE, Ga. - When it comes to breaking the color barrier, there are the firsts you strive for and the ones you hope never happen. Nearly 60 years ago, Claude Mundy made racial history in Atlanta. He became the first black Atlanta Police Department officer to be killed in the line of duty.

It's a tragic story that can be told in two colors: black and gold. And a lesson that guns can be used for both good and evil.

"Some of the people he would lock up in that area would come looking for me and my brother," remembered Mundy's only surviving son Claude IV. "If they caught us, they'd beat us, beat us into the ground! And then go tell us to tell your dad that."

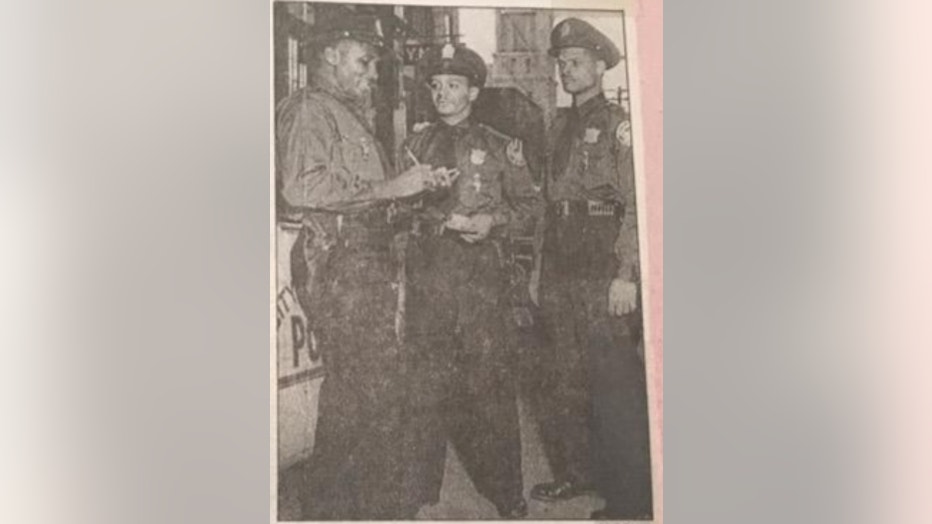

Claude Mundy (R) was killed on Jan. 5, 1961 by an armed burglar he confronted.

Claude grew up often separated from his father, his parents divorcing when he was still a child. Yet the part-time teacher still vividly remembers being the son of one of the city's first black cops. His father was a big man – 6-foot-4, 200 pounds. Always lifting weights. Sometimes ignoring rules that made no sense then or now.

"Black officers were not supposed to lock up white offenders and they would have to hold them until a white officer came," Mundy explained. "But he would lock them up anyway."

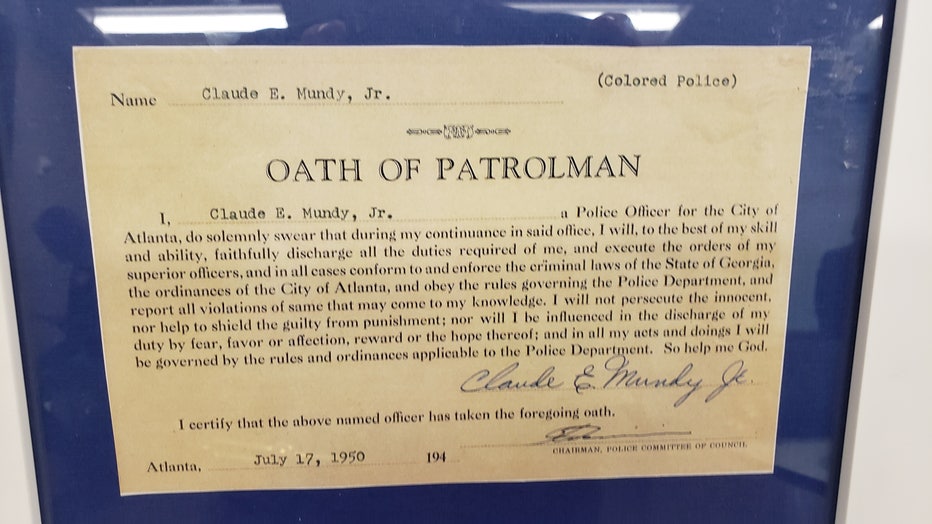

The oath of office signed by Claude Mundy with "(colored police)" prominently displayed in the right corner.

So it's not surprising how officer Mundy answered a burglary call on Jan. 5, 1961. He tackled danger head-on.

His partner Clarence Perry went around to the rear of 572 Parkway Drive. It's an empty lot today, but back then it was the site of a two-story apartment building. An intruder was inside an upstairs apartment. According to police and newspaper reports, Mundy went up the stairs and confronted Joe Louis Pass, 25, also black and whose estranged wife actually lived there. Pass had a small .22-caliber handgun hidden his palm. He shot Mundy in the heart. But before he collapsed, Mundy fired five rounds back at Pass. Both would fall to the ground dead.

Claude Mundy IV was in sixth grade. He can still remember his mother's calming words that night.

"She told me to go to bed, she had to run off and I wouldn't be going to school the next day," he said.

And then later?

"I dealed with it the best I could at the time."

In the early 1970s, Claude would see his dad's .38-caliber revolver again. Now gold-plated, presented to the family by his fellow black officers in a ceremony to honor the first slain black APD cop. But Claude said he and his sister had to give it back that night so the gun could be engraved.

"We never saw it after that," he said. "And the last thing I ever heard about that gun was this thing down in Douglasville."

Nearly 30 years after Mundy had used his service revolver to kill the man who had shot him, the gun had somehow come out of retirement in another county. Now golden but just as lethal. And in the hands of someone who had killed before.

In 1990, a jury convicted Ray Burgess of using the golden gun to commit a string of armed robberies. And one murder.

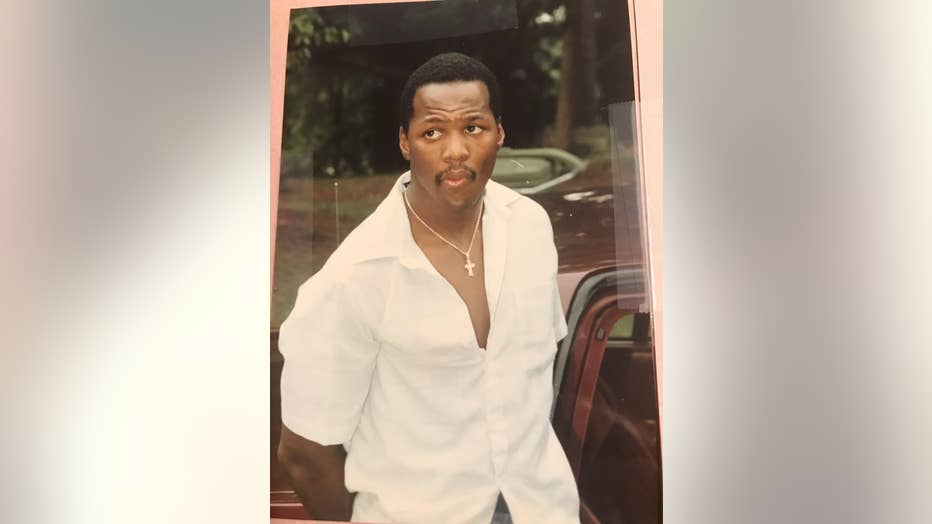

In 1990, a murder parolee in Douglas County went on a crime spree. Ray Burgess pulled off a series of six armed robberies at various hotels. At his last stop, he shot and killed Liston Rue Chunn in front of his family. Every witness told deputies the weapon used was a golden gun. Investigators found it in Burgess' home.

A jury convicted Burgess on all counts. He would cheat the electric chair, though, dying of natural causes while on Death Row.

"It's not often you see the same weapon used for both good and evil," observed current Douglas County district attorney Ryan Leonard.

But how was it ever available to be used for evil? Turns out, the city of Atlanta decided in the 1970s to display Mundy's golden gun in the now-closed Kennedy Community Center. It eventually disappeared and somehow wound up in the hands of Burgess. Investigators heard it had been left in an office drawer at the center. Perhaps no one there realized it was still a working gun.

For the last 30 years, it has sat in a Douglas County evidence locker, until prosecutors decided it was time to send the golden gun home.

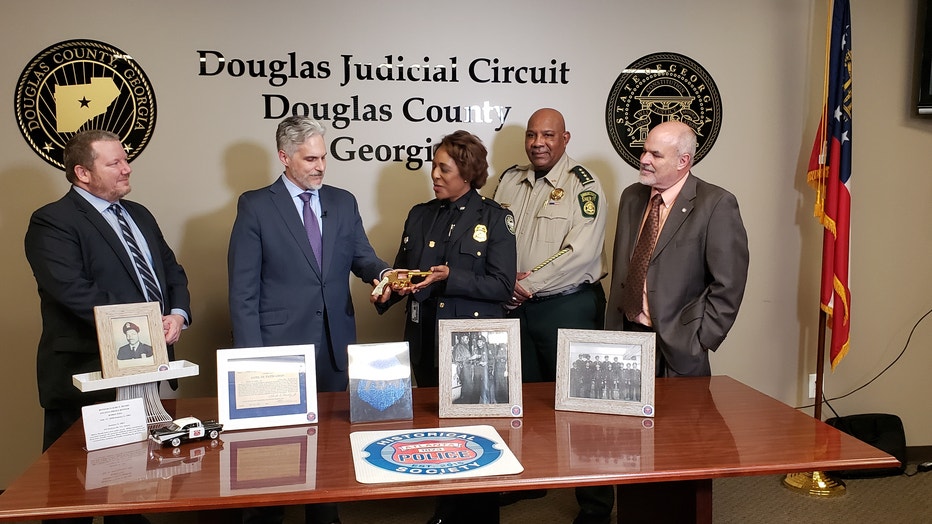

Douglas County DA Ryan Leonard presents the golden gun to APD Historical Society's Tonya Austin. Chief assistant DA Steve Knittel (L), Douglas County sheriff Tim Pounds and DA chief investigator Scott Cosper look on. Pounds and Cosper helped recover

In a ceremony at the Douglas County courthouse, Leonard presented Mundy's gun to retired Atlanta police sergeant Tonya Austin. She heads up APD's Historical Society. Also there were Chief Assistant District Attorney Steve Knittel, Douglas County Sheriff Tim Pounds and DA chief investigator Scott Cosper. Pounds and Cosper originally arrested Burgess and recovered the golden gun.

Despite the family's wishes, the gun will not be going back to the Mundys. Claude wanted to understand why.

"That was the gun that my father had when he was on duty," he pointed out. "If they feel some reason why they should keep the gun, I'd like to know. At least explain why."

Mundy's only surviving son wanted to know why the golden gun wasn't returned to the family instead of APD.

We asked the same question.

"Given the history of how this gun ended up in Douglas County, we would not want a weapon out there that's inscribed with Atlanta police to mysteriously end up where it could take another life," explained Sgt. Austin.

The simple explanation: a gun that was used to kill two people for far different reasons belongs in a museum where the public can appreciate this part of Atlanta history.

And all its complicated colors.