On Jackie Robinson Day, remember the Black men who played in the majors before he broke the color barrier

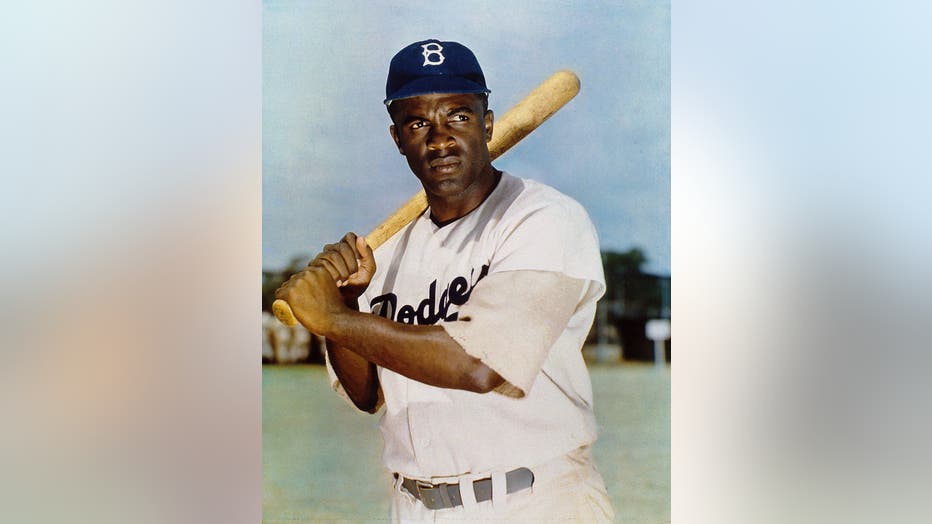

Major League Baseball will hold its annual Jackie Robinson Day celebrations on Thursday, commemorating the man who broke MLB’s color barrier in 1947.

Thousands of players will sport Robinson's iconic No. 42, which has been retired league-wide since 1997.

Ballclubs will post photos thanking him for ending segregated baseball. The Los Angeles Dodgers, Robinson's former team, are sure to outdo them all.

Jackie Robinson in Brooklyn Dodgers uniform. (Photo by Warnecke/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

But little, if any, fuss will be made about William Edward Whyte (White), Moses Fleetwood Walker, Weldy Walker or Bumpus Jones.

While Robinson broke the color barrier — a rule that prohibited Black players from the league — Whyte, Jones and the Walker brothers were Black men in the majors long before Robinson was even born.

And the daunting shadow cast by Robinson’s legacy threatens to reduce those men to footnotes in a seldom-read history book.

William Edward Whyte

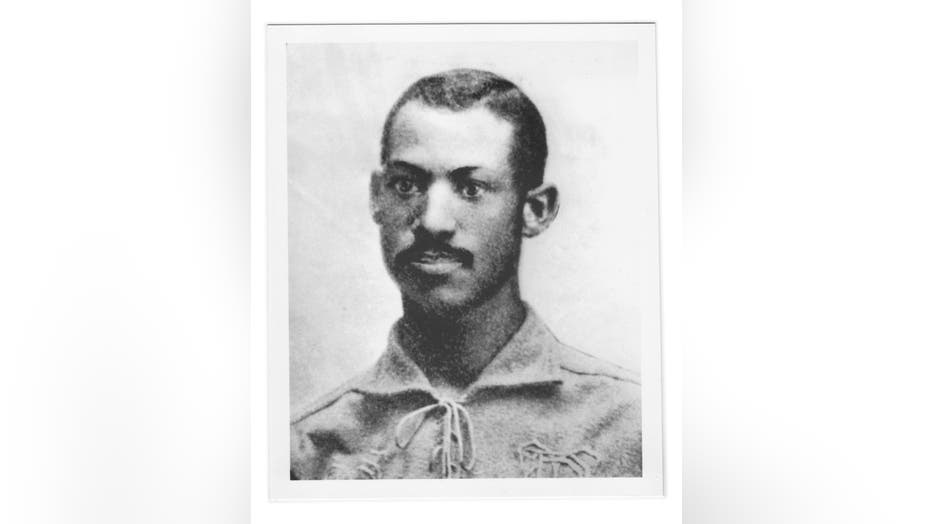

William Edward Whyte (Photos courtesy of James Brunson/Public domain)

Whyte was born in October 1860 to slave owner Andrew Jackson White and a mixed-race woman enslaved by White. Legally, that made Whyte enslaved and a Black man with a very light complexion.

According to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), Whyte used his lighter skin to pass as a White man — a common practice for those wishing to evade the disadvantages of being Black.

While passing, Whyte suited up for the National League’s Providence Grays on June 21, 1879, becoming the first Black man to play in the majors 40 years before Robinson took his first breath and 68 years before the color barrier fell.

"The Grays discovered Whyte while playing against Brown University, where the young baseballist attended school," said baseball historian James Brunson, author of the book "The Negro Leagues Were Major Leagues: Historians Reappraise Black Baseball."

Researchers described his time in the majors as a cameo. He only appeared in one game after replacing regular first baseman Joe Start.

Even so, Whyte finished the game 1-for-4 and scored a run in the Grays’ 5-3 win.

After the Grays, Brunson said Whyte played for three professional Black clubs: The St. Louis Black Stockings (1883), Trenton Cuban Giants (1885-1886) and New York Gorhams (1886).

Around that time, another Black man was making his way into the majors.

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Moses Fleetwood Walker (Photo courtesy of James Brunson/Public domain)

Whyte’s participation in the 1879 game was only discovered within the last decade or so. Prior to that, "Fleet" Walker was believed to have been the first Black man in the majors.

Fleet Walker enjoyed a longer career in the majors than Whyte. He played catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings when they were formed as a Northwestern League team in 1883.

They won the league championship that year and joined the major league American Association in 1884.

On May 1, 1884, Walker took the field for the Blue Stockings — his major-league debut. Toledo lost to Louisville 5-1, and the Courier-Journal seemed to take delight detailing the errors charged to Walker.

The Toledo Evening Bee gave the game less attention — printing the headline "Walker Did It."

Aside from denigration in the press, Walker played the entire season, often the recipient of racist objections to his participation, meal refusals from hotels or abuse from the fans and teammates.

SABR said Tony Mullane, Toledo’s workhorse pitcher, once told the New York Age that he pitched to Walker without telling him what was coming — a particularly daunting task when considering protective equipment for 19th-century catchers was often limited to just a mask.

And the fielding errors charged to Walker might have been the result of a refusal to work with him.

In an excerpt of the 1919 article, Mullane said the following:

"He [Walker] was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals. One day he signaled me for a curve and I shot a fast ball at him. He caught it and came down to me. … He said, ‘I’ll catch you without signals, but I won’t catch you if you are going to cross me when I give you signals.’ And all the rest of that season he caught me and caught anything I pitched without knowing what was coming."

That was life for Walker in the summer of 1884. But he wouldn’t have to endure it completely alone.

Weldy Wilberforce Walker

Weldy Walker (Photos courtesy of James Brunson/Public domain)

Two months after Walker made his debut for the Blue Stockings, his younger brother Weldy followed suit.

Toledo’s roster had become depleted by injuries, prompting the Blue Stockings to recruit Weldy Walker to join his brother.

He appeared in his first game on July 15, driving in two runs with a double to left field. But his big-league career was limited to just four games.

He and Fleet never got to share the field and he was out of the majors by Aug. 6.

The Walker brothers never returned to the majors after the 1884 season.

Brunson said Fleetwood played with several White clubs in the Midwest and East after his stint in Toledo, undergoing even more racially abusive treatment.

Weldy returned to Black baseball leagues, suiting up for squads in Cleveland and Pittsburgh. He dedicated most of his life to activism and even championed the return of Black Americans to Africa — specifically, Liberia, where former American slaves had established a country.

Meanwhile, MLB firmly established the color barrier in 1887, which wouldn’t be broken until the Dodgers brought in Robinson in 1947 — though the career of Bumpus Jones complicates that legacy.

Charles Leander "Bumpus" Jones

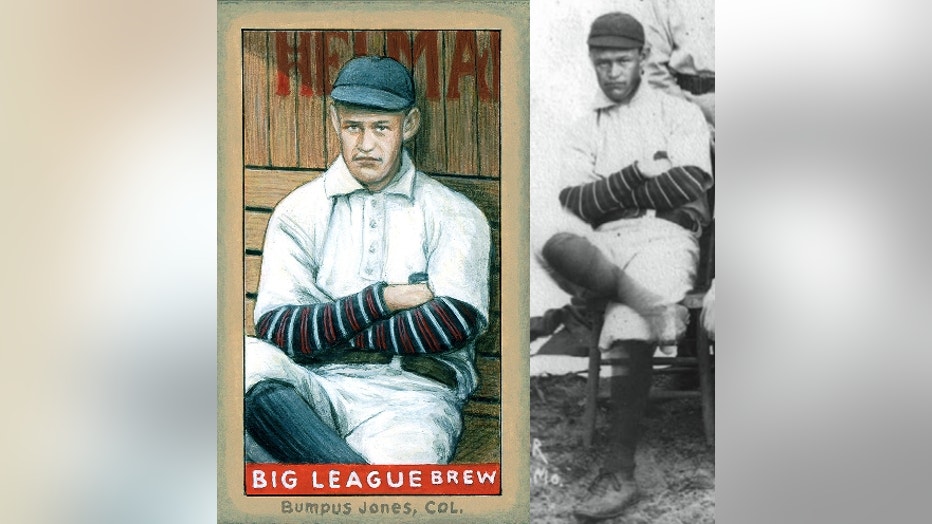

Bumpus Jones (Photos public domain)

Jones lived his life as a White man. His death certificate classifies him as White. And he played in the majors after the color line had been enacted.

Even so, records of his relatives have given rise to speculation that he was, indeed, a Black man passing for White.

According to SABR, research by a relative suggests that his paternal family listed Black or colored in census records and on obituaries. The logic that would qualify Whyte as a Black man would do the same for Jones.

Jones’ debuted for the Cincinnati Reds on Oct. 15, 1892, in grand fashion, tossing a no-hitter in a 7-1 win over the Pittsburgh Pirates in the final game of the season.

His short stint in the majors ended the following year as the young pitcher began to struggle mightily. The New York Giants signed him the next year, giving where he continued to struggle.

He bounced around with a few minor league teams after that, including a stint with the Grays — who had once employed Whyte.

The problem with the term "Major Leagues"

In modern uses of the phrase "major leagues," we think of the National League and American League playing under the MLB umbrella. But Brunson takes issue with the historical use of the term when it is used to minimize the participation of Black baseball players in the 19th and 20th centuries.

"The phrase major league baseball — also a euphemism for White baseball — overshadows historical reality. It wrongly suggests that contemporary professional Black clubs didn’t exist. They did," Brunson said, pointing to squads like the St. Louis Brown Stockings (1870-71), Chicago Uniques (1871-74), St. Louis Black Stockings (1883) and many more.

Brunson acknowledges Whyte and the Walkers as Black players who slipped through the color barrier before it was firmly established. But he said the Black teams of their time complicate their tenure in White baseball.

"Professional Black baseball’s impact on them, its style of play, not unlike the Negro Leagues on Jackie Robinson, has been ignored or trivialized," Brunson said. "Historians haven’t been kind."

That’s an issue the modern-day MLB is working to rectify. On Dec. 16, 2020, Commissioner Rob Manfred classified seven Negro Leagues that operated between 1920 and 1948 as major leagues.

RELATED: MLB: Negro Leagues were a major league

The Negro Leagues receiving the distinction, which were responsible for 35 MLB hall of famers, included the following:

- Negro National League (I) (1920-31)

- Eastern Colored League (1923-28)

- American Negro League (1929)

- East-West League (1932)

- Negro Southern League (1932)

- Negro National League (II) (1933-48)

- Negro American League (1937-48)

"All of us who love baseball have long known that the Negro Leagues produced many of our game’s best players, innovations and triumphs against a backdrop of injustice," Manfred said in a statement. "We are now grateful to count the players of the Negro Leagues where they belong: as Major Leaguers within the official historical record."

MLB made that move thanks to the work of historian Larry Lester, a co-founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City — as well as Scott Simkus, Mike Lynch, Gary Ashwill and Kevin Johnson for their construction of Seamheads’ Negro Leagues Database.

"For more than 3,400 players, very few of whom are alive, their families will now be able to say their records were included among white Major Leaguers of the period," MLB’s official historian John Thorn said. "There’s no distinction to be made. They were all big leaguers."

RELATED: Panel recommends 7 Negro Leagues for major league status

But the distinction does nothing to recognize the Black professionals who played in the 1800s. MLB said Black leagues prior to 1920 were not considered because they lacked league structure and were ultimately unsuccessful.

Brunson said the legitimacy of the broader legacy of the 19th century Black leagues has not been seriously studied.

"While research is often difficult and frustrating, the historical evidence is available for well-intentioned scholars," he said.

Brunson contends that professional Black baseballists emerged immediately after the Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1869 — and holds hard-throwing pitcher B. Blanch as the earliest Black professional.

"If [Fleet] Walker’s legacy is under-appreciated, so is the legacy of 19th-century professional black baseballists," Brunson said. "I am interested in retrieving players and clubs from the dustbin of history, and putting them into proper historical context."

This story was reported from Atlanta.