To cut or kill: Higher gas prices force community to confront costs of each

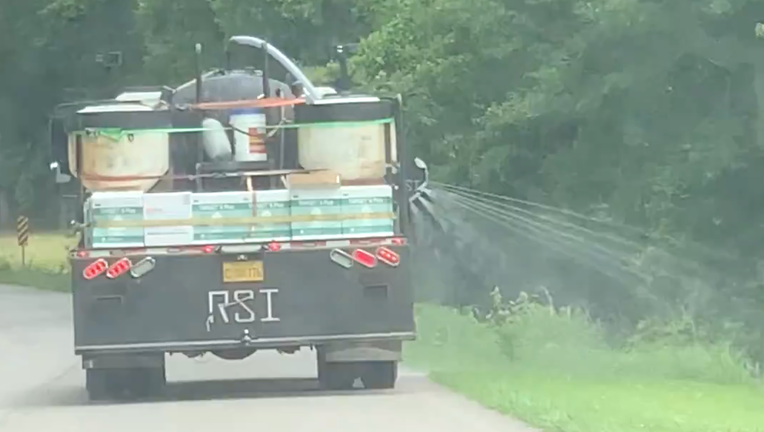

A contractor sprays herbicides to kill the weeds in Cleburne County, AL. Opponents argue the poison also kills helpful plants and wildlife. (image from Melanie Spaulding)

HEFLIN, Ala. - Higher fuel prices helped convince one community to make a big change to how it handles roadside weeds.

Cleburne County, Alabama has decided it’s cheaper to kill than to cut.

Instead of mowing, twice a year an outside contractor sprays poison along the 367 miles of blacktop.

Spraying herbicides cost the county $129,000 each year. Commission Chairman Ryan Robertson estimates it would cost $220,000 to mow.

"I’m not an advocate myself," he said. The chairman only gets to vote in a tie. The decision to spray was 3-1.

"They thought people like the spraying and the roads look neater," he said.

But not all the people.

Biologist Melanie Spaulding points out how spraying has killed helpful plants but allowed non-native invasive weeds to come back even stronger.

"They’re killing off plants in certain areas that are causing unsafe roadways," complained Melanie Spaulding, a biologist and freelance botanist who two years earlier agreed to catalog the area’s fauna for free.

She said plants that stabilize the banks are being killed forever, while the non-helpful plants quickly recover.

"You can’t kill non-native invasive plants just by going and spraying because they come back even stronger," she said. "So the more that they spray, the more organisms they’re killing, both plants and animals that can affect the erosion here."

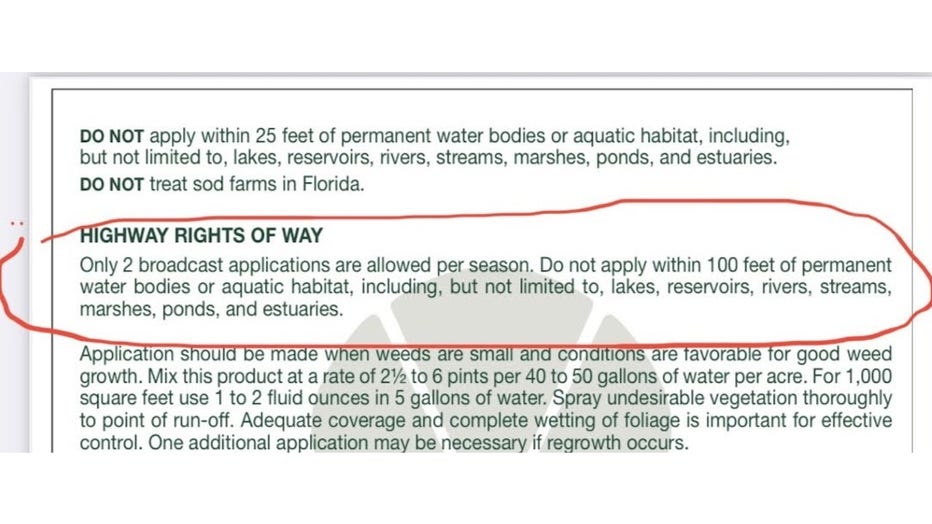

The contractor, IVM Solutions of Auburn, Alabama, used a diluted mixture of Target 6 Plus Herbicide. The use label warns "do not apply directly to water or to areas where surface water is present…. Do not apply within 100 feet of permanent water bodies or aquatic habitat…"

Last summer Spaulding followed one of the spray trucks, recording video of the contractor spraying the herbicide over creeks and other water areas.

The Alabama Department of Agriculture placed IVM Solutions on a one-year probation and fined the company $500.

IVM Solutions did not return a request for comment.

However, county leaders rehired IVM Solutions for another year.

"We learned a lot," Commissioner Roger Hill explained at a February meeting. "And we’ve got a plan that we plan to go with this year. Do things differently. Smarter. A better approach."

No spraying signs sprang up across the county.

Tommy Mix sure hopes so.

Shortly after the first spray treatment last year, the Muscadine beekeeper noticed his hive had collapsed.

"I went out one morning to check them, the whole house was dead," Mix, 31, remembered.

Especially troubling for Tommy because he lives with autism. Raising bees for their honey is a major part of his structured day.

"When they get sprayed they immediately get confused as to where their food’s at … where their home’s at," he explained. "They cannot find their way back to the colony."

Tommy Mix blames the spraying for the sudden collapse of his bee colony last year but admits there's no solid evidence other than timing.

He admitted he has no direct evidence the spraying is the culprit, but the timing was suspicious. His family said they’ve also noticed fewer turtles, frogs and snakes since the spraying began.

Some Cleburne County residents are already on edge about what they believe to be a cluster of cancer cases in one area.

Across the state line in Georgia, Haralson County does not use herbicides to control their roadside weeds.

They cut "exclusively," said Linda Ledbetter with Haralson County Public Works.

In Cleburne County, the second spray of 2022 is expected to start in June.